The long and winding road of TikTok Shop

How Bytedance's TikTok took a page from the Douyin's e-commerce playbook but faced challenges abroad

Things that caught our attention

How TikTok moved into (cross-border) e-commerce

TikTok’s struggles with live commerce in western markets

Things that caught our attention

Our Tech Buzz China writer Ed Sander picked up his China study tours where he left them when China closed its borders in 2020. He delivered a very well-received tour to a group of Dutch retail specialists in October. At Tech Buzz China, we are considering putting together one or more study tours in the near future. If the idea appeals to you, please fill out this short survey and let us know what you would be most interested in.

A few years ago, Meituan tried an unsuccessful Hema (Freshippo) clone called Ella/Xiao Xiang ('little elephant'), as we described in Need for Speed 3: Coming soon, from a Meituan warehouse near you! These supermarkets were shut down in 2019, but Meituan continued to use a green version of the logo for Meituan Maicai ('grocery'). Now, Meituan has changed the name of its front-end warehouse business, Maicai, to Xiao Xiang Supermarket. It is supposed to emphasize that Meituan delivers 10.000 SKUs and not just 'fresh products'. (source)

Meanwhile, Meituan Maicai’s main competitor, Dingdong Maicai, has opened its first offline store in Shanghai: Dingdong Outlet. The store is not meant to offload unsold products but to create an offline channel for Dingdong’s growing selection of direct-sourced products. (source) Read more about Dingdong in Need for Speed 2: Can the front-end warehouse model ever be profitable?

The "Instant Retail Industry Development Report 2023" by the Ministry of Commerce shows that the scale of China's instant retail industry reached 504 billion yuan in 2022. It is expected to grow to 3 times that size in 2025 and 5 times in 2026, far exceeding expectations. Read more about instant retail in Need for Speed: Instant Retail.

Pinduoduo’s cross-border webshop Temu has launched maritime shipments. Not only will this reduce logistics costs by 30-60%, but there are also shortages in air cargo: in 2023 demand is growing 9.5% and supply only 5.7%. Meanwhile, the vessel utilization rate is only 75% (dropping 6% from last year). Expect Temu's delivery times for some products to become longer, but not as long as you might think: Matson ships from Shanghai to Long Beach in 11 days. (source)

Alibaba Cloud suffered two system outages in a month and the third one in 12 months. (source) Didi and Tencent recently also experienced outages. Read more about Alibaba Cloud in Rain or Shine for Alibaba Cloud?

Introduction

In this new edition of Tech Buzz China Insider, we have a deep dive into TikTok Shop for you. After a short delay in our two-week publication schedule, this brings us back on track.

The first section, which is free to all subscribers, tells the story of TikTok’s first steps into e-commerce in the UK and US in the period 2021-2022. It features text from a series of articles that Tech Buzz China contributor Ed Sander previously published on ChinaTalk.nl. The section closes with a fragment of a presentation Ed gave about Chinese cross-border e-commerce platforms in early 2023. Watch this video summary if you are pressed for time.

The second part consists of an update on developments in other regions and the activities of TikTok Shop in the US in more recent months. It also includes a detailed look into TikTok’s different operating and sales models and the implementation of the fully managed model specifically. This section is only available to paying subscribers.

We hope you enjoy this deep dive.

Freya Zhang, Ed Sander & Rui Ma

(click on the images above for information on the Tech Buzz China team)

How TikTok moved into (cross-border) e-commerce

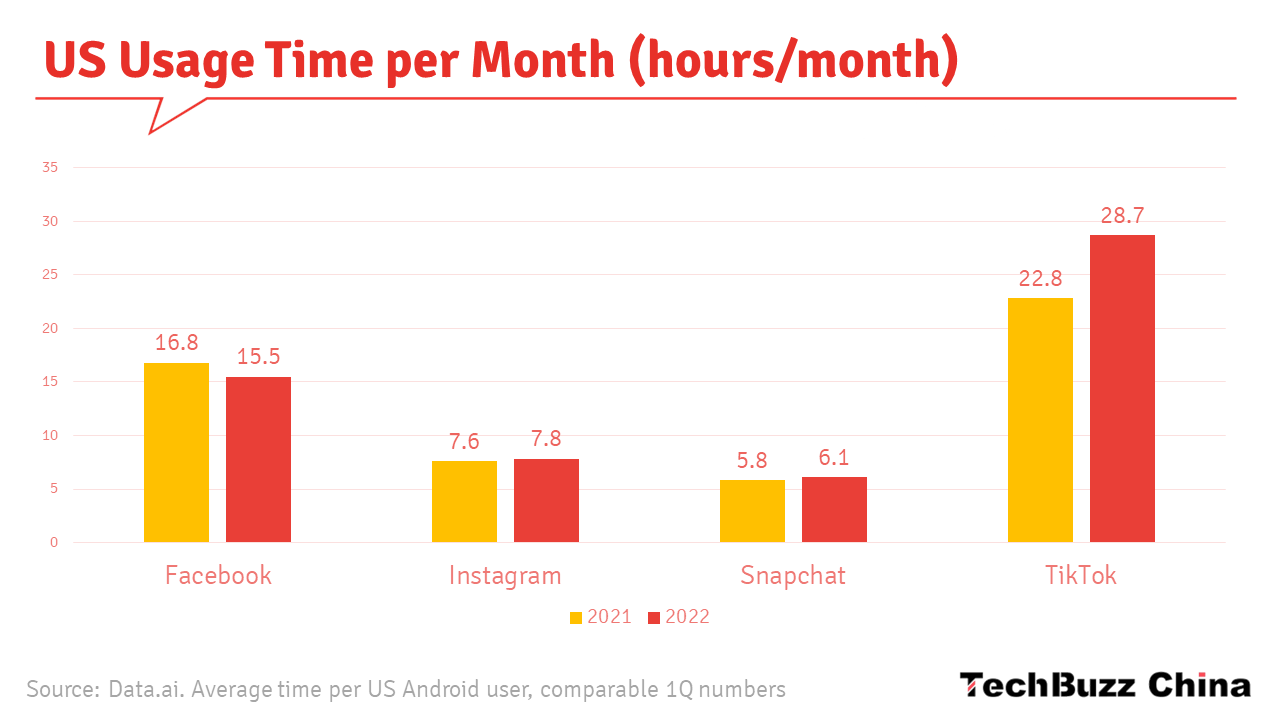

TikTok was launched in 2017 and gained traction in 2018, quickly becoming one of the most popular global apps, with 1 billion global users in September 2021. On average, a U.S. user spends about 29 hours per month on TikTok, surpassing the combined user time on Facebook (16 hours) and Instagram (8 hours). However, Facebook and Instagram still have a larger user base. [1]

In the past years, TikTok’s main monetization model has been advertising, with revenue from this source adding up to approximately $4 billion in 2021 and exceeding its goal of $10 billion in 2022. [2]

Meanwhile, Douyin, TikTok’s sister app in the Chinese home market, has been experimenting with various models for e-commerce since 2018. In that year, it started generating traffic to external webshops like Alibaba’s Taobao and JD.com. In 2020, it severed its ties to these external platforms and rolled out its own in-app e-commerce infrastructure. It has been very successful at that, growing its market share in China’s e-commerce market from less than 0.5% in 2019 to 8% in 2021 and is expected to grow this to 14% by 2025, mostly at the expense of market leader Alibaba.

Considering TikTok’s success in user penetration outside China, it was only a matter of time before Bytedance would try to replicate its domestic e-commerce initiatives in TikTok, thereby diversifying its monetization and no longer solely depending on advertising, like many Western apps still do.

Partnerships

As with Douyin in China, TikTok started its e-commerce ventures by teaming up with third parties that run their own e-commerce infrastructures. In October 2020, it partnered with Shopify, allowing Shopify merchants to build TikTok advertising campaigns from their Shopify dashboard. Video ads were automatically generated for selected products, driving traffic from TikTok to their Shopify stores. [3]

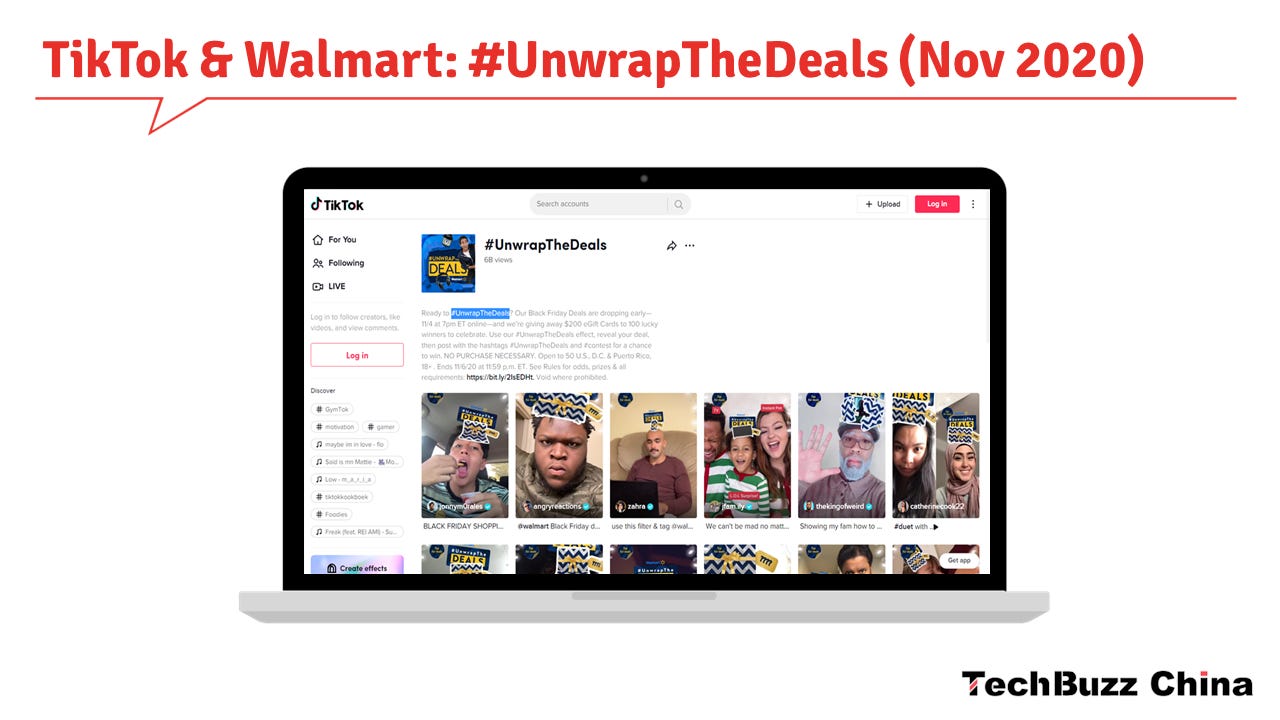

Shortly after, on November 8th 2020, Walmart ran a TikTok campaign called #unwrapthedeals, cooperating with TikTok creators to generate traffic to the Walmart website by clicking a button on the screen. According to the retailer, creators made over a million videos for the campaign, and it generated 5.5 billion views.

At the time, Walmart was a potential party in a possible forced sale of TikTok to the retailer and Oracle, initiated by the Trump administration. This never came about, as Bytedance managed to stall the negotiations long enough for the newly arrived Biden administration to scrap Trump’s executive order.

In December 2020, the Walmart partnership was extended to a test with TikTok’s first ‘shoppable livestream’, an attempt to recreate China’s popular live commerce trend in the US, using TikTok creators to promote apparel products. As with the #unwrapthedeals campaign, users were taken out of the app to the Walmart website if they wanted to buy products. Shoppers would have a separate check-out process, requiring setting up a user account if you didn’t have one yet. Considering how, at that time, e-commerce was already fully integrated in Douyin, it felt far from seamless.

Turner Novak’s recording of the Walmart purchase process on TikTok.

Although Walmart didn’t share specific sales results – only saying the stream had seven times more views than anticipated and that it grew its TikTok follower base by 25% – it called the test a success. Walmart held another one-hour TikTok livestream in March 2021, this time focusing on beauty care products. [4]

In August 2021, TikTok expanded its partnership with Shopify and launched TikTok Shop in the US, UK and Canada. [5] Shopify merchants with a TikTok for Business account could add a shop page to their TikTok profile and synchronise their Shopify item catalogues.

In September 2021, a comparable partnership was announced with Square, a US digital payment company. [6] Besides creating a shop with Square x TikTok (with actual sales taking place on Square), the connection also allowed for product links to be created in their TikTok videos that forward shoppers to a merchant’s Square webshops. Other partners TikTok expanded the shopping connection to were Ecwid and PrestaShop.

At the time, many of these partnerships reminded us of one of the first phases of e-commerce on Douyin when the app would forward traffic to external marketplaces like Taobao … before eventually cutting those ties and setting up its own e-commerce infrastructure. It seemed obvious what would happen to those partnerships if TikTok’s own e-commerce platform started taking off…

And that proprietary infrastructure was already being tested elsewhere…

Launching TikTok Shop

In early 2021, TikTok began testing e-commerce features in Indonesia and the UK. In February 2021, TikTok launched Seller University, a training hub to help merchants do business on the app. It was later rebranded as TikTok Shop Academy and rolled out to various countries in Southeast Asia. [7]

At a marketing event called ‘TikTok World’ in September 2021, TikTok presented in-app storefronts for brands and launched full-service e-commerce. [8] In November 2021, TikTok launched a stand-alone app for merchants in Southeast Asia to manage their TikTok stores. [9]

By this time, there were two ways that TikTok facilitated shopping in the app. First, there was the TikTok Storefront, which was used in the Shopify and Walmart examples from the US. In the Storefront model, products were visible in TikTok, but the transactions were completed on the third-party platform. Second, there was the TikTok Shop, in which transactions are completed in the app, and TikTok took a 5% commission. The first approach was called ‘semi-closed loop’ while the latter was ‘full-closed loop’.

Many Chinese merchants opened shops on TikTok, seeing it as an alternative to platforms like Amazon, especially after the latter started cracking down on fraudulent sellers. In November 2021, Bytedance started incentivizing merchants from Guangdong to sell to consumers in the UK through TikTok. Besides free commission on the first 90 days, they would receive various other benefits, like free shipping. [10]

But it wasn’t easy.

When Chinese merchants decided to promote their products through livestreams, they had three options: use their own staff, hire Chinese who can speak fluent English to make content or use locals in their target markets. This last option can be prohibitively expensive considering the higher wages in the target market. Still, the language skills of Chinese often leave much to be desired. A host with bad communication does not help build trust in purchasing from the concerned merchants. As a matter of fact, it puts more emphasis on its often-considered controversial origins.

Some Chinese teachers of the English language who had become jobless after the Chinese government banned after-school tutoring in the summer of 2021 were now working as livestream hosts. [11] Their language skills were a clear advantage, although many lacked good sales skills. They also weren’t as passionate about selling to an invisible audience as they were about teaching a foreign language to kids.

Another challenge was the delivery times. The cross-border logistics between a Chinese seller and a UK buyer were handled by different service providers for each of the three steps: the shipment from merchant to domestic warehouse, domestic warehouse to UK warehouse and UK warehouse to UK consumer. The last step was done by Royal Mail, and the full process could take 10 to 30 days.

In November 2021, TikTok rolled out its first live commerce streams in the UK for Black Friday. [12] One of the brands participating in a 3-hour broadcast was Charlotte Tilbury. The cosmetics brand offered special low prices during the livestream, a tactic that is one of the success factors of this type of e-commerce in China. The livestream had ‘over 500 viewers’ at its peak, which, compared to Chinese standards for livestreams, didn’t seem all that impressive. Another merchant, electronics seller TheTechHead, claimed to have sold £100.000 in its stream on the 25th.

December 2021 saw TikTok UK try another live commerce event called ‘On Trend’. [13]

Meanwhile, the share of local sellers kept growing. Before August 2021, only 10% of TikTok UK’s total e-commerce sales came from local UK merchants. By the end of 2021, this had risen to 50%. [14]

And then things got serious…

In January and February 2022, TikTok was holding weekly webinars to explain e-commerce on the app. TikTok also launched a new TikTok Shop Academy website for the UK and a UK seller Whatsapp group.

Image source: TikTok

Of course, to get users to start buying in the app, you first need a large number of TikTok Shops with lots of products. In January 2022, it became clear how much TikTok UK wanted retailers to use the app as a sales channel. Small businesses were invited to open an in-app shop, and the 13 top sellers would get awarded monthly prizes ranging from £1,000 to £10,000. [15]

Sellers could also win up to £3,000 in vouchers if they would do up to 30 livestreams of 2 hours each per month, incentives and subsidies that are very common in China. TikTok also subsidised some of the discounts that brands were giving, as well as the costs of livestreams, like studio space and technical staff. [16]

On top of these incentives, TikTok also lowered the commission on sales from 5% to 1.8% for the first 90 days of new TikTok Shops and offered £1,000 rewards for referrals of new merchants.

TikTok’s struggles with live commerce in Western markets

In February 2022, it was reported that TikTok had reached RMB 6 billion in GMV (~€880 million) in its global e-commerce business (excluding China, where sales are recorded under Douyin) in 2021. [17] More than 70% of these sales originated in Indonesia, the rest in the UK. TikTok was aiming to double this GMV in 2022. By comparison, the e-commerce GMV on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, in 2021 was estimated to have been RMB 800 billion (~$110 billion). [18] The daily GMV of TikTok for the UK was about the volume of one medium-sized live commerce shop in China. [19]

Average daily sales of TikTok UK in June 2022 were only around $300.000. [14] TikTok had set itself a goal for global e-commerce sales of RMB 3 trillion (~€240 billion) in GMV within five years. At roughly three-quarters of the global GMV of Amazon, an almost three-decade-old company, that seemed unrealistically ambitious.

Struggling live commerce

On July 5th 2022, the Financial Times dropped a bomb with an article claiming ‘TikTok abandons e-commerce expansion in Europe and US‘. [20] The article specifically mentioned live commerce as the initiative that had failed to gain traction in the Western test market of the UK.

At home, Douyin had tripled live commerce sales year on year. According to sources of the Financial Times, TikTok’s plans to expand to Germany, France, Italy, and Spain in the first half of 2022 and the US later in the year were shelved. TikTok denied the news, stating that it had no plans for a roll-out of e-commerce to other regions in Europe and that it was still focussing on making it a success in the UK. [21]

Reactions among China tech watchers were sceptical, claiming the article was ‘inaccurate’ and ‘misinformed’ and that it was unlikely TikTok would fully abandon live commerce but would probably prioritise investing in other initiatives. Cailian Press claimed that sources at Bytedance said TikTok would refocus on its development in India, Malaysia, Thailand, Japan, South Korea, and the Middle East while shrinking its business in other regions. [22]

Despite incentives to live-streamers and brands, sales had indeed been disappointing. In the Financial Times, an anonymous TikTok employee was quoted saying: “The model doesn’t work because it is a different market and ecosystem in the UK, but management doesn’t listen and refuses to make changes. (..) It will only work if the company is willing to listen about how to do it in a culturally acceptable way that works for British brands and consumers.” According to an anonymous TikTok employee, the market was simply not ready for live commerce yet. [16]

Long delivery times and lousy service

Pingwest reported that the main problems of TikTok Shop were the faltering logistics and customer service of cross-border sales from China. [23] It quoted a TikTok employee as saying: “Good customer service, after-sales support, and reliable logistics can help platforms create a good shopping experience, build a solid reputation, and boost sales. Cross-border logistics are now too time-consuming, and supporting services are not ideal—all of these contribute to a bad experience for customers.”

According to a LatePost article, Bytedance was trying to solve the problem of long delivery times with a plan called ‘Aquaman’ (海王). [24] It called for setting up UK warehouses to enable e-commerce fulfilment, comparable to Amazon’s ‘Fulfilment by Amazon’ model, in which it stores and distributes sales for merchants on its marketplace for a fee. Products with stable sales would be stored in these UK warehouses to shorten delivery times to 3-5 days. Merchants would send goods to a central warehouse in China that would handle transport to the UK hubs.

TikTok started testing with a Fulfilled by TikTok Shop (FBT) in November 2022 and rolled it out in August 2023. [25]

Image source: TikTok

Another problem customers faced was that Chinese merchants refused returns and refunds. The margins on products were simply too low, and the logistical costs to ship goods back to China were too high. Instead, merchants tended to negotiate a discount.

There was another possible reason for the difficulties live commerce was having on TikTok. [26] The app is largely algorithm-driven; TikTok chooses the content for the users, and it is hard for an influencer to build strong relationships on TikTok. On top of this, in the short, thirty-second videos that make up most of TikTok’s ‘For You’ selection, it was hard for influencers to convince users to actively follow them and watch their longer livestreams. Influencers were saying it was easier to build up loyal followers on platforms like YouTube, and some started moving to other streaming services.

This reminds us of what we have seen happening in China. Live commerce hosts on Taobao and short-video app Kuaishou tend to have much higher GMVs than those on Douyin, simply because Kuaishou is much more built around relationships between hosts and their followers and less by algorithmic recommendation engines.

Culture clashes

On top of the lack of traction of live commerce, TikTok was facing many other challenges in its e-commerce division in the UK. In June 2022, the Financial Times reported that the Chinese working culture at TikTok’s e-commerce division had caused a staff exodus. [16] Sources mentioned a Chinese-style ‘996’ working culture (long days of 12 hours, six days a week), ‘relationships built on fear’ and unrealistic targets of up to £400,000 per livestream (most ‘successful’ streams only generated £5,000).

LatePost published more details on the struggles of TikTok’s e-commerce business in the UK. [14] Frictions existed on both sides: employees in China were dissatisfied with being paid less for the same work, while workers on both sides disliked having to work unconventional hours to accommodate each other’s working schedules. English staff complained about their Chinese managers’ poor language skills, authoritative management styles allowing little participation in the decision-making (‘we decide, you implement’), and confusion caused by frequent changes in organisational structure and work objectives.

Most first and second-level managers in the TikTok UK e-commerce business unit were Chinese, and more Chinese staff had been added, changing the initial Chinese-to-English ratio of the division from 1:9 (comparable to TikTok UK’s full staff) to 5:5. A staff member told LatePost: “Chinese leaders who have never been to the UK and who can’t speak English well are managing a group of project managers with 5-7 years of experience who do not understand Chinese, have never been to China, and have always grown up in the UK environment.”

The first wave of resignations at TikTok’s UK e-commerce division took place between November 2021 and the start of 2022. A second wave followed in May 2022, after staff had received their year-end bonuses. Despite many people leaving, the team still counted about 300 employees and seemed to still be recruiting. In mid-2022, LinkedIn showed many e-commerce-related job openings at TikTok’s London office.

Time was scarce for TikTok; it was facing continuous geopolitical pressure, especially in the US, where politicians continue to call for a ban on TikTok. Meanwhile, TikTok’s user growth has started to slow down in many markets and competition from other Chinese cross-border platforms was increasing.

Being the most valuable unicorn, Bytedance was doubtlessly also contemplating an IPO and needed to make its international performance look good. Mid 2022, Bytedance saw its valuation drop by 25% in private investments. [27] Reports on job cuts at TikTok in the US, UK and EU continued, even though layoffs of an estimated 100 people only represent 1% of its workforce. [28]

What works at home might not work abroad

One of TikTok’s problems seemed to be that it took a strategy from China and expected it to work abroad as well. However rolling out the highly successful tactic of live commerce in China has not brought the expected results in the UK.

One of the success factors for live commerce in China is the ability of a popular host to negotiate substantial discounts from manufacturers and brands because they reach millions of consumers and can thereby guarantee a certain sales volume. However, European brands were uncomfortable with the levels of discounting TikTok was asking for. Brands did not want to disrupt their price system for a new channel with limited sales and an uncertain future. [14]

In February 2022, William August, the founder of a marketing company for live commerce, published an explainer video on TikTok shopping on YouTube. He was – obviously – very enthusiastic about the prospects of live commerce. But watching his video, you can’t help but notice the numbers in the top right corner of the examples of livestreams he was showing, representing the number of people watching the stream. In his video, they range from 4 to 54, with one exception of 166. They might not be representative, but do you think that’s enough to get the amazing discounts the maker of the video was talking about?

Another reason for the lack of success of live commerce is that influencers would rather make well-paid short videos for a brand than spend tiresome hours livestreaming with little potential pay, even if TikTok offers them a flat fee compensation.

Much of the context that makes live commerce successful in China is absent in Western markets, where TikTok is trying to make it successful. In China, live commerce is extremely popular among citizens in smaller cities and rural areas where retail infrastructure is often limited. These circumstances have been one of the main drivers for the success of e-commerce in China, and live commerce is simply an advanced form of e-commerce.

The concerned online shoppers from these markets have more time and less disposable income compared to those in bigger cities (according to data by Fastdata, 75% of buyers on live commerce earned less than RMB 5.000, or €700 per month). Hence, they are always keen on grabbing a discounted product that has been preselected by the livestream hosts’ teams and is thereby guaranteed to be of high quality.

Add seamless integration of e-commerce in Chinese apps, skilful hosts that know how to sell and a ‘fear of missing out’ on good deals, and you have all the ingredients for successful live commerce in China. Not only is this cultural context missing in the West, but we are also still more used to targeted searching and buying on websites (‘shelf commerce’) than making impulsive purchases while watching long livestreams.

Source: Tech Buzz China Livecast with Jordan Berke

Level playing field

Another challenge for cross-border e-commerce from China is the changing policies in Western markets that try to create a more level playing field. More and more often, Chinese platforms are being subjected to the same regulations as those for domestic players in Europe and America. AliExpress’ sales in Europe came under pressure after the EU scrapped the maximum value of €22, at which packages from outside the EU were exempt from value-added-tax. Previously, this meant that most of the low-cost goods from China could be sold through cross-border e-commerce without paying value-added tax. Now, value-added tax and possibly customs clearance fees would be added to the price of purchases from China. A purchase that would previously be priced at €10 on a Chinese platform might now be double the costs.

Chinese cross-border merchants are also facing increased postage costs in the coming years. Under the 1969 system of ‘terminal dues’ of the Universal Postal Union (UPU), China was considered a ‘group III’ developing country and therefore paid lower international postal fees. This has made it ridiculously cheap for Chinese merchants to send postage packages around the world. When, in the past decade, the amount of cross-border e-commerce sent by mail from China increased, the US started to run a net deficit in international mail. In Europe and the US, e-commerce companies complained that was more expensive for them to ship in their own countries than it is for Chinese companies to deliver from the other side of the world.

The US threatened to pull out of the UPU, which compromised by allowing postage fees to increase by 164% between 2020 and 2025. This will either hurt the margin of the e-commerce merchants or result in higher consumer prices.

Chinese platforms are also being forced to make their terms and conditions compliant with regulations in the European market, like the right to return products within 14 days of receipt. Europeans can now file a dispute with a court in their home country instead of only in China.

In the meantime, consumer rights organisations continue to warn about inferior quality and unsafe products sold on Chinese platforms. A 2022 consumer survey by a Dutch consumer rights organisation found that almost one-third of respondents had bought products on webshops outside the EU that did not meet expectations . [29]

Short presentation on TikTok Shop in 2022 by Ed Sander

(Note: the section below is only available to paid Tech Buzz China subscribers)