Table of contents

Things that caught our attention

The cracks were already showing in 2019

Things that caught our attention

Alibaba announced its Q2 2023 results, with total revenue reaching RMB 234.16 billion ($32.3 billion), showing a 14% year-on-year increase (although, remember, cities like Shanghai were in a lockdown a year ago). The logistical division Cainiao, preparing an IPO, saw profit for the first time (RMB 877 million). (source) We recently wrote extensively about Cainiao in Alibaba Cainiao: Delivering Innovation, Globally?

We recently published Redefining Fresh: Alibaba's Freshippo and the New Frontier in Grocery Business, an article about Alibaba’s retail chain. If you want to learn more about Freshippo (Hema), head over to ChinaTalk.nl, where our team member Ed took an even deeper dive into the 10+ different formats that Alibaba launched under the brand umbrella in a four-part article.

Douyin local services GMV exceeded 100 billion yuan in the year's first half. While this was behind the target of 290 billion for 2023, GMV has picked up recently and was 30 billion yuan in July. (source) In March, we wrote an extensive report about Douyin’s local services business in Food Fight! Douyin’s local services business.

Cotti Coffee, the coffee chain of former frauding Luckin founder, has opened 5000 stores in 7 months. (source) Meanwhile, Luckin Coffee (6.201 billion yuan) has overtaken Starbucks (5.96 billion yuan) in revenue in China for the first time in the second quarter of 2023. (source) At the end of the quarter, Luckin had 10,836 stores, while Starbucks China had 6,480 stores. One of our upcoming reports will explore Cotti’s business and the coffee war. Stay tuned!

DingTalk will split off from Alibaba Cloud and becomes a separate ('N') company in the 1+6+N set-up. The enterprise chat app will have to survive on its own while a financial burden is released from Alibaba Cloud, which will eventually seek an IPO. (Source)

Tencent released revenue data for advertising in WeChat Channels for the 1st time: it exceeded 3 billion yuan in Q2 2023. User time of Channels almost doubled YoY. (Source) Earlier this year, we wrote about WeChat's counterattack on Douyin and Kuaishou with Channels in WeChat Channels - The Hope of Tencent.

Introduction

This week we have something a bit different for you. One of our team members, Ed Sander, has been offering study tours to China since 2018 through ChinaTechTrip. These tours focus on digital innovation, e-commerce and new retail and combine master classes and excursions. Back in 2019, Ed used to take tour participants to many physical appearances of the new retail craze. During his field research for the tours in 2019, he noticed how cracks had started appearing in some of the new retail initiatives.

After waiting three years during the zero-Covid travel restrictions, Ed returned to China to update the program of his upcoming study tour. During his location scouting for the new tour, he visited new interesting concepts and checked on the status of concepts he had included in his pre-Covid tours.

This Tech Buzz China article combines earlier articles he wrote about the faltering of certain new retail concepts in 2019 (available to all readers) with a visual exploration of its current state (available to paying members). We think it offers a rare ‘on the ground’ perspective on some hype that started in 2016.

We hope you enjoy this deviation from our regular content and learn something about taking the PR of Chinese internet companies with a grain of salt.

Freya Zhang, Ed Sander & Rui Ma

(click on the images above for information on the Tech Buzz China team)

Alibaba’s New Retail Hype

In the past months, Tech Buzz China has been exploring two relatively successful forms of new retail: Alibaba’s Hema (Freshippo) supermarkets and instant retail (home delivery in 30-60 minutes after ordering online). New retail was a term first coined by Jack Ma in 2016 and, according to some reports, was an idea of Daniel Zhang, who recently gave up his CEO position at Alibaba Group to focus on Alibaba Cloud (which we wrote about this year).

Alibaba described it as follows: “New Retail (..) uses technology to merge online and offline shopping into one comprehensive channel to benefit consumers and brands. For those consumers, New Retail means added convenience and fun, whether buying through an app or at a physical store. For merchants, the model offers a holistic view of their customers’ shopping patterns both online and off. These insights help brands more precisely target their product offerings and marketing campaigns.”

On October 13th 2017, CEO Daniel Zhang wrote in a letter to shareholders that it was not the growth of online sales that would offer the best future for the company but helping traditional retailers upgrade to the New Retail model. Before long, Alibaba started hyping New Retail in videos and articles on its Alizilla website. New retail was the best thing since sliced bread…

New Retail was also more than just Alibaba. JD.com unfolded initiatives under the moniker ‘Unbounded Retail’ while Tencent called it ‘Smart+ Retail’. Many O2O models, unmanned stores, gimmicks and gadgets were unleashed on the retail world. Back in 2018, when I did a keynote about what was happening in New Retail, I used the following four categories:

Shops where online and offline are connected (e.g. Hema)

Optimisation of the logistical chain. Examples are Alibaba’s Lingshoutong 零售通 or ‘Retail Integrated’ and JD’s Xin Tong Lu 新通路, both of which connected independent pop-and-mon supermarkets to the internet companies’ wholesale systems.

‘Retailtainment’ (making shopping more fun through gadgets and gamification)

Intelligent Self-Service concepts (e.g. unmanned stores)

In 2018, I started putting together a study tour for Dutch retailers wanting to learn more about what was happening in China. When both the Editor in Chief of Alizilla and a ‘Tmall New Retail Service Operation Advisor’ I had been in contact with started giving evasive answers when I asked them for some examples of new retail stores, I started having suspicions. It was almost like they didn’t want me to go there.

So instead, I did my own research, locating the stores from the press releases and travelling to Shanghai, Hangzhou and Beijing to visit them. And I found out a possible reason why they preferred me to stay away…

The cracks were already showing in 2019

As part of my work as a study tour leader, I do a lot of location scouting. China’s New Retail featured heavily in my tour programs since it had high levels of interest outside China and was one of the more visible and easily accessible aspects of Chinese digital innovation. Something that wasn’t just online, and you could actually show people in the real world.

I have visited over 100 new retail locations in Shanghai, Beijing, Hangzhou and Xi’an, evaluating them for our tour programs. But since the retail sector is highly versatile, I often revisit locations I have used before starting a new tour. You wouldn’t want to take your customers somewhere and have to say: ’Oh, that’s strange; there was a really interesting store here just a few months ago!’

When double-checking these locations, I often found that some stores had disappeared or remarkably changed. In the last tour I delivered in 2019, I had to replace 25% of the locations I had selected just months before. Post-covid, in 2023, I had to replace 50% of the program I delivered in 2019.

The learnings I gained from this field research were invaluable. After all, you always read about the shiny new concepts launched but rarely about how some fail miserably. And I believe that we can learn as much from the failures as from the successes. This article shares my findings during on-the-ground location scouting in 2019 and 2023 through text and many photographs I have taken over the years.

Tmall Small Stores

In 2017, Alibaba launched its Lingshoutong 零售通 or ‘Retail Integrated’ program. The program created partnerships between independent convenience stores and pop-an-mom supermarkets, of which there were 6 million in China. Alibaba would upgrade these stores with the latest technology and share product recommendations based on their online customer knowledge about customers in the store’s neighbourhood. In return, the stores would procure their goods on Alibaba’s Ling Shou Tong wholesale platform.

A shop used in Alibaba’s PR campaign from early 2018 concerned the convenience store Weijun in the company’s hometown of Hangzhou. It was one of the participants in the Lingshoutong program that had been chosen to become a Tmall Small Store (天猫小店) or ‘Tmall Corner Shop’ as the campaign called them.

The shop was used as an example of how Alibaba turned messy and old-fashioned pop-and-mom shops into bright and shiny professional convenience stores. As part of the campaign to promote their ‘Retail Integrated’ approach, Alibaba widely circulated a set of ‘before and after’ photographs of the store and made a promotional video about the shop’s facelift. The promo clip seems has been removed from Alibaba’s YouTube channel but is still available here.

The new shop was bright, organised and came with an impressive LED signage. According to a report by Axios in June 2018, Weijun was doing well financially, having increased its revenue by 30%.

Having read about the shop in 2018, I decided to visit it when I was in Hangzhou a year later. I located the store using its Chinese name, Baidu maps and the address that can be seen in the pictures below. When I arrived, I first thought I’d made a mistake. I walked back to verify if I was in the right street and closely compared the pictures from the press releases to what I saw. I noted that the concrete planters and larger street number 418 were no longer present, but the sign with street number 420 still was. Yes, the store in the location on the map was indeed the famed Tmall convenience store; it had the same name.

But there was no LED screen (in 2023, I would find out why) and inside the shop was messier than the one in the video and pictures. With a little effort, you could still see the bright Tmall Weijun store from the PR messages through the clutter on the counter, stacked up boxes and the outdated Singles Day advertising in the shop. Since that shop’s facelift, it seemed to have fallen victim to the ‘organised chaos’ common in China’s pop-and-mom shops.

Weijun convenience store before 2017, in 2017 and 2019.

We shall return to Tmall Weijun in 2023…

Tmall (Co-Branded) Smart Stores

Most of the time, I would find potential locations to visit during our tour through news sources about New Retail initiatives. More often than not, this would concern skilfully crafted press releases by Alibaba on their promotional website Alizila. Ever so often, the real thing fell short of the expectations that these slick videos and articles created. And frequently visiting the same locations over time and seeing the changes that had taken place (or had been absent) gave me a good understanding of what worked and what didn’t. Many of the technological gadgets introduced as one of the aspects of New Retail clearly fell in the latter category.

A good example is the Tmall Smart Store (天猫智慧门店, Tianmao zhihui mendian). In 2018, Alibaba began cooperating with important Tmall Global merchants to create these co-branded New Retail megastores. They would be packed with ‘intelligent’, ‘AI-driven’ tools to improve consumers' shopping experience. These brands would undoubtedly pay a substantial fee to have their shops equipped with cloud shelves, game screens and AI mirrors.

Let’s have a look at how some of these stores sailed in the years 2018 and 2019.

Tmall Intersport

In 2018, Intersport’s Beijing store was the first Tmall Smart Store to be launched (read the original press release here). ‘Tmall Intersport’ could be found in the popular Qianmen shopping street, south of Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. The store's location seemed far from optimal, though, as it was located west of the main shopping street, hidden behind a line of souvenir shops. You might not have seen it if you were not specifically looking for it.

The choice of location is not only remarkable because of the poor visibility but also because the type of store didn’t quite fit in with the various restaurants, souvenirs and snack shops found in Qianmen. This might be why there never seemed to be much store traffic on the six occasions I visited the store.

As the name implies, Tmall Intersport was a collaboration between Alibaba’s e-commerce platform Tmall and the sportswear retailer Intersport. Tmall provided all the technology in the shop, creating a clear offline-to-online link with Intersport’s shop on Alibaba’s Tmall e-commerce platform. The longtail of Intersport’s product range could be browsed on so-called cloud shelves (云货架, Yun Huojia), and after scanning a QR code, products could be ordered online and delivered to your home address.

Another technology highlighted in press releases about Tmall Intersport was the product displays that ‘spontaneously’ showed information about a shoe when you take it off the shelf. At least … sometimes that’s what happened. At first, I thought the technology worked through image recognition by the cameras above the screens, but when several sports shoes did not trigger any response on the screen, I decided to ask a shop assistant for help.

It turned out that the technology was a lot less advanced. The screens were activated by ‘beacons’, Bluetooth transmitters attached to the shoes. The problem, however, is that these were only attached to half of the shoes on display. As a result, the screen would respond to one shoe, while another left the customer wondering why the interactive screen stopped functioning.

I also had doubts about the gamification screens at these retail locations. On the second floor of the Tmall Intersport store, visitors could create their own cartoon of a basketball game and send it to them after scanning a QR code. Pretty cool, even though the image quality left much to be desired. But that same game was present ever since the store's launch in May 2018 until the last time I visited it in October 2019. When a store doesn’t update its gamification gimmicks frequently, customers have no real incentive to return when they’ve tried it once.

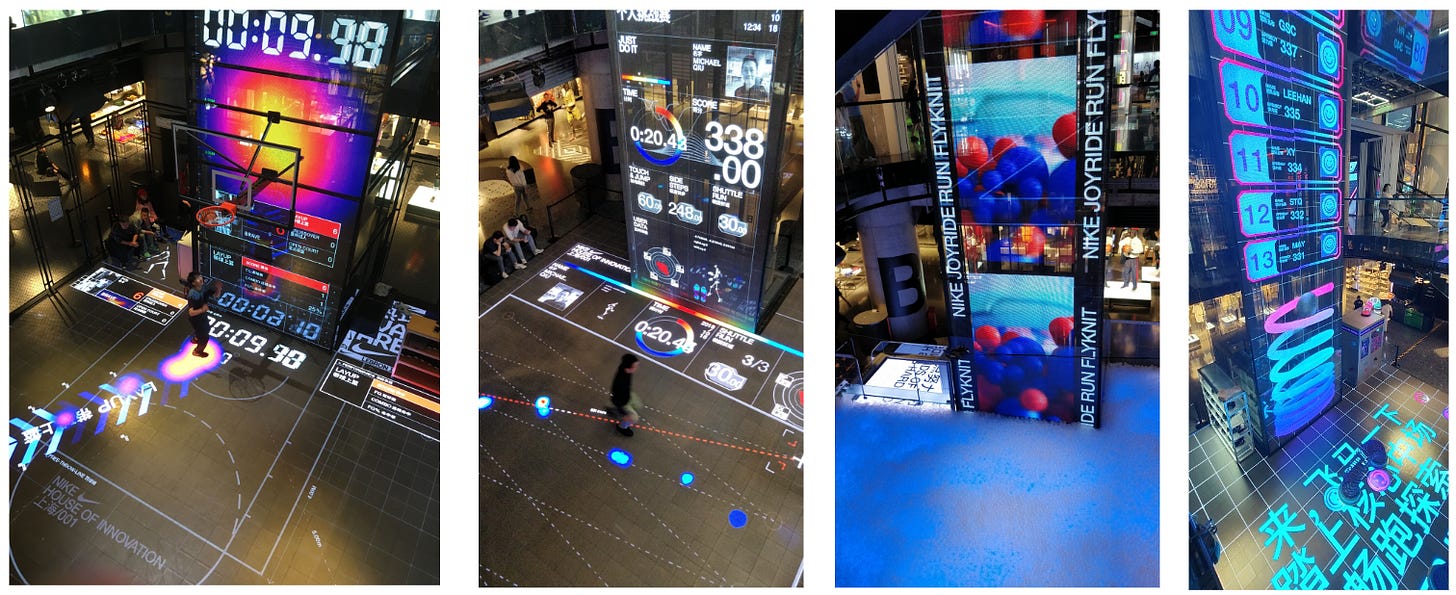

The same goes for many other gadgets that might make tech-savvy Chinese consumers curious; they might come to try it once but will quickly lose interest. Nike’s House of Innovation flagship store on Shanghai’s Nanjing Road seems to understand this and changes its game in the basement play court several times a year, supporting new campaigns and product introductions.

Doing gamification right: different games in the Nike House of Innovation in Shanghai on different visits.

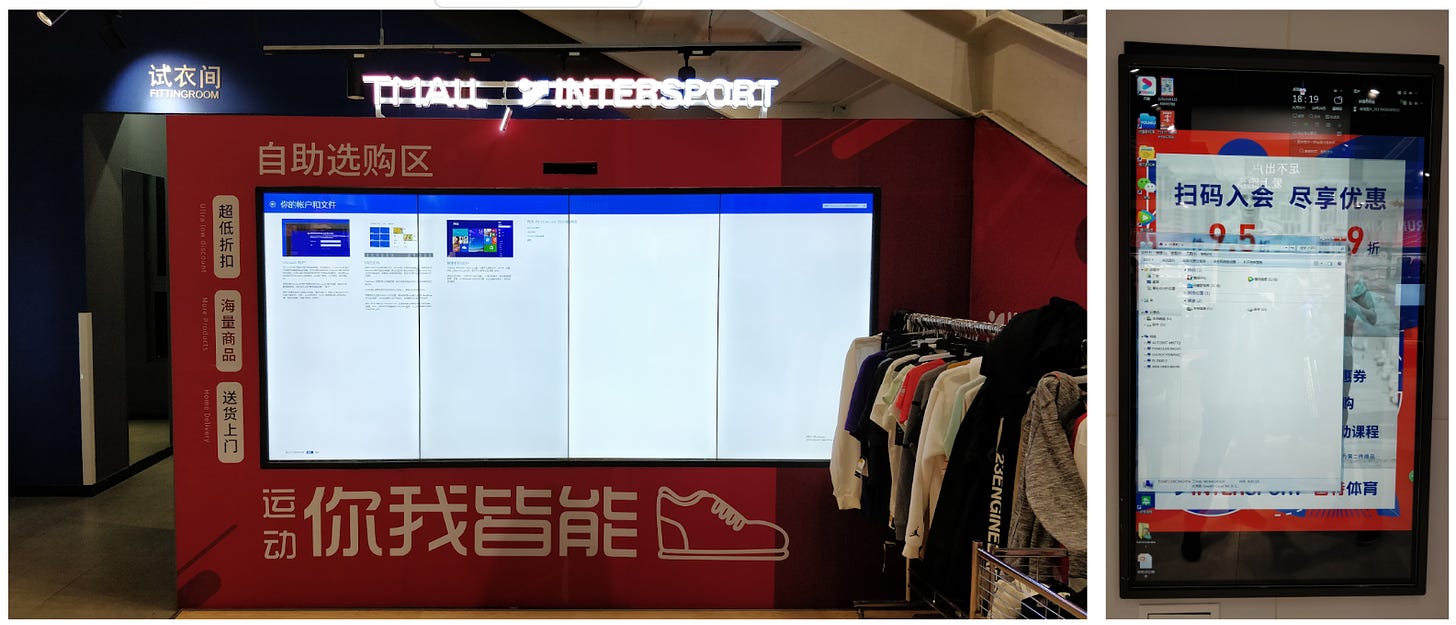

The Tmall Intersport shop also had the much-hyped cloud shelves. The idea behind these was that you could browse all available products, including a longtail of SKUs not present in the store. After scanning a QR code, you would be redirected to the Tmall store of Intersport, where you could order a product for home delivery.

But on one of my visits, they just showed files on the store’s server, enabling me to browse around without the staff raising as much as a brow.

The whole Tmall Intersport experience was just a dodgy affair, up to the ‘Lorem Ipsum’ dummy text on the poster next to the door …

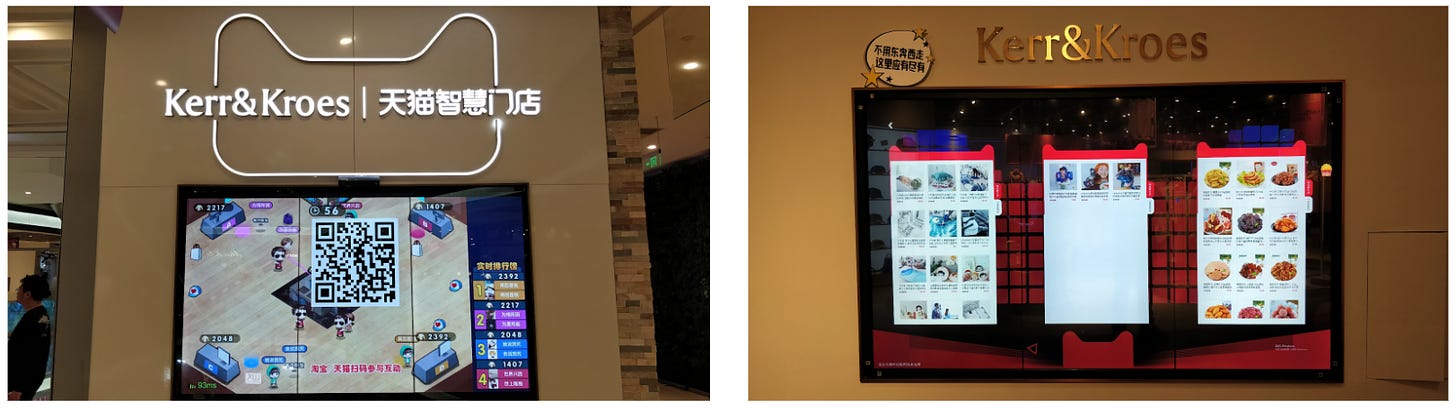

Tmall Kerr & Kroes

In early 2019, I visited another Tmall collaboration with fashion brand Kerr & Kroes in Shanghai’s Joy City shopping mall. The shop was quite remarkable for its many cloud shelves, magic mirrors and video games, but I couldn’t help noticing that, even on busy weekends, the store traffic was limited.

The store had a claw machine that gave you three tries after scanning a QR code and following the store’s WeChat official account, a way to gain followers. But there seemed to be very few views on the actual messages that this account posted.

Games, cloud shelves and magic mirrors at Tmall Kerr & Kroes.

When returning five months later, it seemed like all Alibaba’s mirrors and all Alibaba’s cloud shelves could not save Tmall Kerr & Kroes. The shop was closed, and the roller screen had a note saying it was ‘temporarily closed for internal adjustment’. I have seen signs like that before in China. More often than not, they mean that the shop is closing down permanently. And even more remarkable, there seemed to be no more sign of the Tmall co-branding.

Left: me, according to a magic mirror. Right: Tmall Kerr & Kroes, temporarily closed for internal adjustment.

Magic mirrors

Tmall Kerr & Kroes and Tmall Intersport both had the much-discussed ‘magic mirrors’. I also found them at an offline store of Xiaohongshu and In Alibaba’s shopping Mall Qinchengli in Hangzhou.

PR messages had us believe that the mirror would scan your body, after which you could virtually try on various items from a shop’s assortment. Indeed, the animation on the screen made you believe that your whole body was being scanned. But the only recognizable part of your physique you would see in the mirror afterwards was a picture of your face on a standard torso, regardless if you were thin or obese.

Maybe these mirrors were trying to be polite, but the person in the mirror might not necessarily resemble reality. In my case, I got to see my long-lost slender twin brother.

Users had to adjust their height and posture in the mirror through different sliders to make the image resemble them. They could then project products from the shop’s assortment onto that image. That range of products was sometimes frustratingly limited, so you would quickly get bored of the magic of these mirrors.

(Nobody) Home Times

In Hangzhou, I headed for Alibaba-invested Home Times, a shop announced in October 2017 as ‘Alibaba’s Vision of the Furniture Store of the Future’. Home Times was supposed to have large interactive TV screens (云货架, Yun Huojia) that customers could use to view products in a virtual home setting. When interested in a product, shoppers could scan a QR code to order it online and have it delivered to their home.

At the Home Times store inside Hangzhou’s Yintai shopping mall on Yan’an Road, I wanted to try these screens. Arriving there, I only found deep blackness staring back at me from the turned-off screens. I explained to the staff that I was a writer and study tour leader and would like to try these interactive screens. The shop attendant went away, probably to consult a manager, only to return a minute later to tell me the screens could not be turned on for me and would only be active during certain times of the day. But when I returned later during the day, they were still turned off…

The interactive screens at Home Times showed little interactivity.

Tmall Innisfree

As the home base of Alibaba, there was more to be found in Hangzhou. In July 2018, a press release by Alibaba announced how an Innesfrfee store had been ‘rejuvenated by New Retail’. And indeed, this shop of the Korean beauty brand had interactive shelves that would play a video for a product you picked up and a cloud shelf with the full Innesfree assortment available in its Tmall store.

But the magic mirror that let you virtually try out make-up and the ‘smart skin analyzer’ that evaluated the condition of your skin and gave advice on the right skin care products were often shut off. My question, if I could perhaps try it out, met with a comparable response as at Home Times.

When I later visited the store with a tour group, we convinced the staff to turn the skin analyser on. Judging from the effort that it took, the thing probably hadn’t been used for ages. And sure enough, when one of the ladies in the group tried it out, the screen’s system crashed. I hope it wasn’t her skin causing that…

No skin was analysed today.

Visiting all those Tmall Smart Stores made me wonder how successful all these new technological gadgets were when shops didn’t even bother to turn them on. Meanwhile, gadgets like magic mirrors and cloud shelves had featured prominently in Alibaba’s PR about Innisfree, Home Times and Tmall Intersport only a year earlier.

A shop assistant at Xiaohongshu’s offline store has to turn a magic mirror on for us. (Shanghai, 2019)

Shop assistants probably noticed that the mirrors lost their novelty value quickly. On my second visit to the Xiaohongshu store, across from Tmall Kerr & Kroes, the staff didn’t even bother to turn their magic mirror on anymore. On my third visit, they removed their magic mirror and interactive screens. And nowadays, the offline Xiaohongshu stores have gone the same way as their magic mirrors and fully disappeared.

Unmanned stores

Let’s leave the Tmall co-branded stores behind and move on to another concept of the new retail hype: unmanned stores.

Throughout 2018 and 2019, I visited many different unmanned store concepts, including the ‘Auchan 1 Minute’ by supermarket chain Auchan (part of Alibaba-invested Sun Art Retail), the JD X unmanned store from e-commerce player JD.com, Suning’s Biu and the GGV-capital-invested and -promoted BingoBox.

Let's look at how these concepts seemed to fare in 2019.

Auchan 1 Minute

The French Auchan was a hypermarket chain that was part of Sun Art in China, in which Alibaba has invested heavily. In recent years Sun Art has rebranded all Auchan stores to RT-Mart, another hypermarket brand Sun Art operates.

Auchan's strategy to make stores unmanned mainly seemed to focus on speed. Instead of walking through the store and queueing at the checkout for a small purchase, such as a drink or snack, you could use the Auchan 1 Minute. I've seen two versions of it, a container-like store outside an actual Auchan hypermarket and a mini-shop-in-shop in front of the entrance inside the supermarket itself. With both types, you could pay by self-scanning the products using WeChat or Alipay instead of your bank card (click here for a demo video).

Auchan 1 Minute unmanned shops in front of (left) and inside (right) the Auchan supermarket.

Both variants that I had previously visited in Shanghai turned out to be gone in September 2019. Several other unmanned Auchan stores in Shanghai and Hangzhou had also disappeared into thin air. Still wanting to show one to a tour group, I couldn't believe my luck when I found an Auchan 1 Minute strategically placed near a Holiday Inn in an industrial estate. It was well-stocked, but after scanning the QR code and hearing the familiar click of the electronic lock, the shop turned out to be closed with the mechanical lock.

It didn’t surprise me that Auchan 1 Minute didn’t seem to be a great success. The Auchan 1 Minute competed with various convenience stores such as Familymart and 7/11, which can be found everywhere in the streets of major Chinese cities nowadays. Buying a drink or snack is faster at such a store than at Auchan's container.

However, Auchan's concept of unmanned shops did not seem to have completely disappeared. After a long search, I found another operational Auchan 1 Minute in Beijing in a residential community, where competition was probably more limited.

An Auchan 1 Minute in a residential community in Beijing.

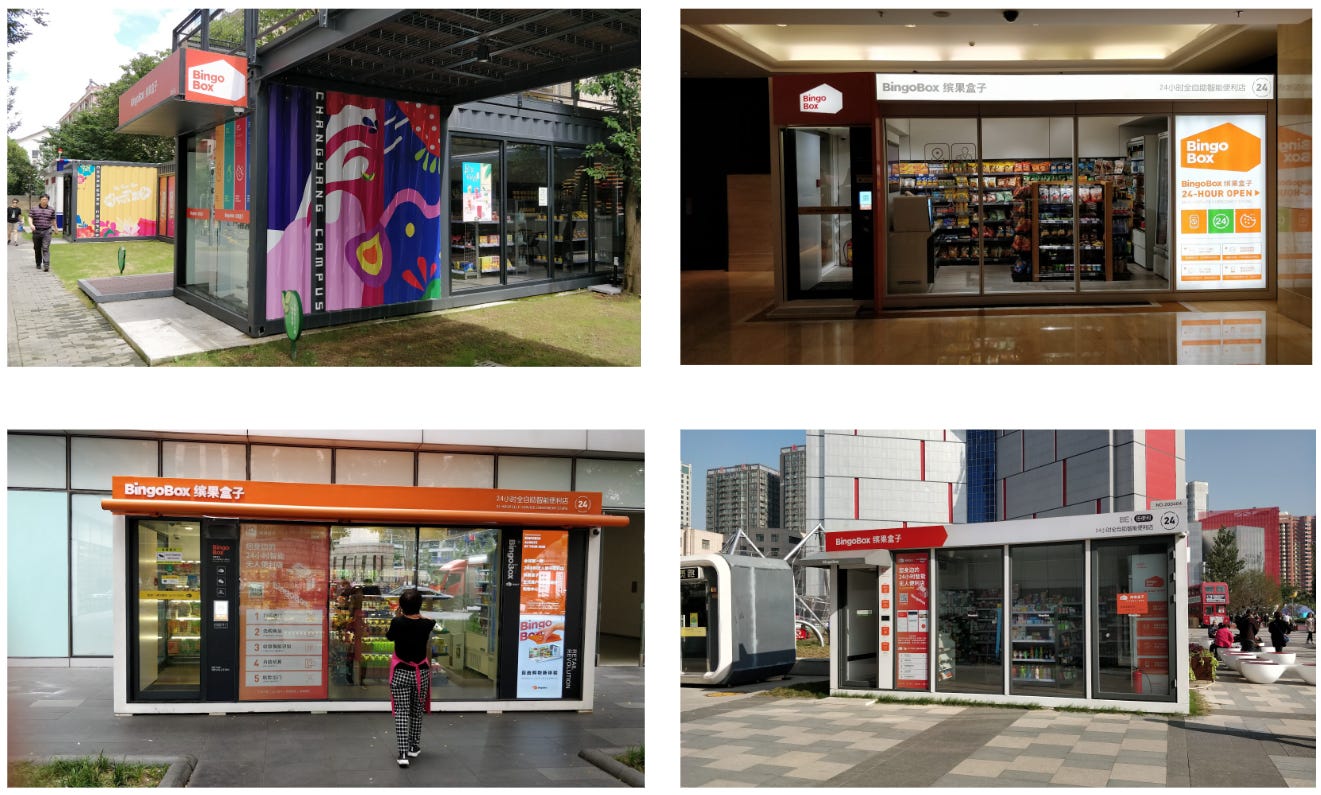

BingoBox

When the company started in 2016, BingoBox had big plans: to open no fewer than 3,000 unmanned stores in China. Three years later, not much had come of that goal. As of September 2017, the company had 158 boxes in 22 cities. The CEO of BingoBox told me in 2018 (link in Dutch) that 500 stores had been opened.

According to information on BingoBox's website, they operated in 28 cities by the end of 2019, only six more than two years earlier. BingoBox told (since suspended) WeChat blog Ran Caijing in 2019 that they once operated in 40 cities but had to close several unprofitable boxes. The company also appeared to have withdrawn from southern China by that time.

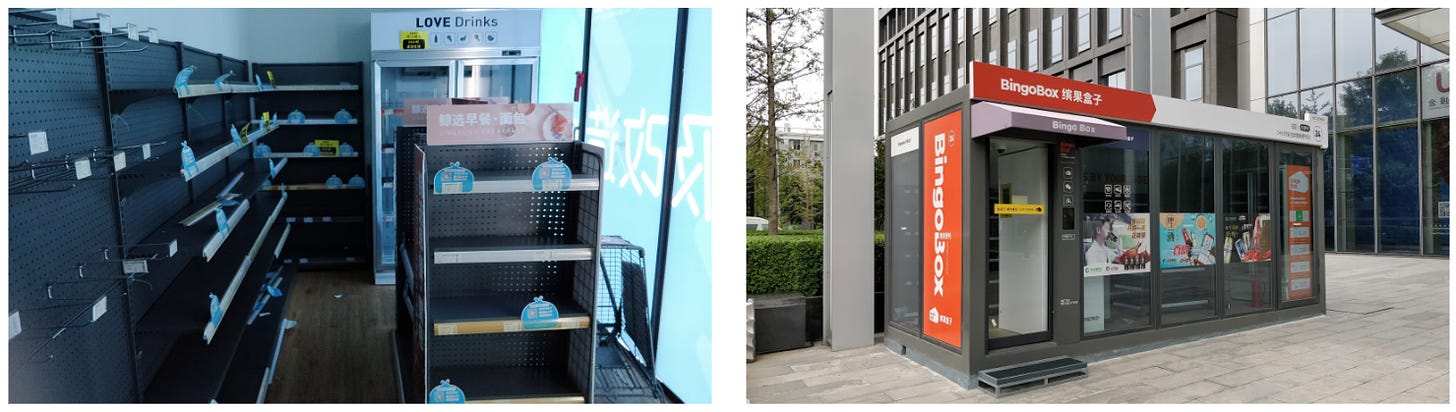

Outside Beijing, where the company had 35 BingoBoxes according to its app, the boxes were few and far between. When I consulted Chinese apps like Dianping or Baidu Maps, I usually only found a handful in other cities. And often, they proved to have disappeared or were empty when I visited those locations. I could usually deduce from the lack of recent reviews for a box that it was probably no longer operational.

In Shanghai in 2019, I found a BingoBox on the Changyang campus, next to a juice stand with a robot arm and a container where you could play table tennis after scanning a QR code. It was still in the late days of the sharing economy craze…

The store was very spacious inside, but it didn’t use all that space efficiently, and the number of different products was disappointing.

I was surprised by two other locations where I found BingoBoxes. There was a BingoBox in the back of the lobby of the New Century Grand Hotel in Hangzhou, and I also found two in the huge complex of the Hangzhou International Expo Center. The company seemed to be experimenting with strategically chosen locations with high traffic but no direct competition from convenience stores in the immediate vicinity.

BingoBoxes at Shanghai's Changyang campus (top right), the New Century Grand Hotel in Hangzhou (top left), Beijing's financial district (bottom left), and Xi'an's Coffee Space (bottom right).

But despite finding these BingoBoxes, it became clear in 2019 that things weren’t going as planned. In Hangzhou, I found a BingoBox next to a large Century Mart supermarket, the door turned out to be unlocked, and the shelves were eerily empty. I came across another abandoned Bingobox in Beijing’s financial district.

Abandoned BingoBoxes in Hangzhou (left) and Beijing (right).

Ran Caijing's article from June 2019 revealed a lot about the state of affairs at BingoBox. According to the company, the operating costs for a box were only 15% of those of a regular convenience store; 2,500 RMB ($318) versus 15,000 RMB ($1,900).

However, according to employees, the start-up costs of a box were 80,000 RMB (over €10,000) and with a daily turnover of 1,000 RMB (€127), the unmanned store had a payback period of approximately two years. As of September 2018, there were 293 boxes, and only 40 had a turnover of more than RMB 1,000 daily. 108 Boxes saw less than 300 RMB turnover daily. Some boxes were profitable, but the company as a whole was still loss-making, partly due to the huge cost of R&D and technology.

In the meantime, after two investment rounds, investors were no longer eager to pump extra money into the company. BingoBox received no further funding after the last $80 million capital injection in January 2018. A former employee told Ran Caijing that there had been several rounds of layoffs at BingoBox since October 2018, and the number of employees had fallen from 500 to 100…

JD X Unmanned Store

The term ‘unmanned store’ is never completely correct since staff are always linked to these stores. Think of logistical supplies, customer service, etc. The CEO of Bingobox had told me he could manage 40 stores with five people. Normally these people should be relatively invisible to the shoppers; you should not encounter clerks or cashiers in unmanned stores.

But at the JD X unmanned stores, I often found a remarkable number of employees present. After observing the stores for a while, the reason became clear. Despite the extensive explanation of how these shops work on the outer walls, many consumers did not yet understand how to gain access. They tried to enter with their usual QR code in WeChat, not realising they needed to first register in a separate JD app or JD X-mini program in WeChat.

The store clerk present often had to explain how the stores should be used. On one of my visits to a JD X store, I even found myself explaining a desperate Chinese couple how to enter the store. I told myself the need for additional staff would probably be temporary until the consumer was used to these concepts. But the implementation was definitely not as smooth as you might believe based on the press releases.

The choice of locations for these unmanned stores didn’t always seem to be well-planned. In Beijing, I visited two JD X unmanned stores. One was located on the ground floor of an office building in the Jianguomen district. This one seemed to be doing relatively well; whenever I visited it, some office workers were getting themselves snacks. The other one, located in Huanyu Plaza shopping mall, drew much less traffic (watch a demo video here).

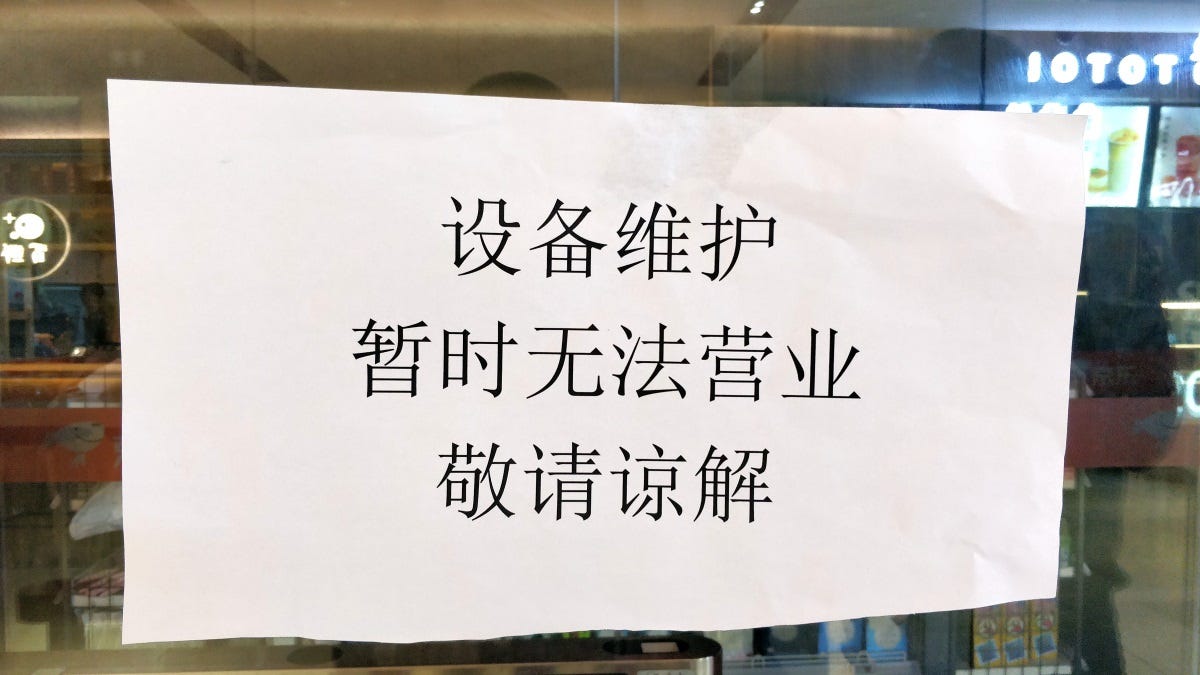

Upon my second visit to the store in Huanyu Plaza, a sign on the window claimed it was temporarily closed for maintenance. We’ve seen that before, haven’t we?

Temporarily closed for maintenance of the equipment. Thank you for your understanding.

Sure enough, when I revisited Huanyu Plaza a few months later, the JD X shop was gone. That didn’t surprise me since the store had been located right next to a Yonghui Superspecies supermarket. Unlike the JD X store in the office building in Jianguomen district, where no other convenient stores were present, the JD X store at Huanyu Plaza had to compete with a neighbour that offered a much larger assortment.

But even the JD X in Jianguomen district did not survive. It proved to have been completely converted on a visit in late 2019. All RFID and facial recognition technology had been removed from the store in favour of a clerk and simpler self-scanning like in most convenience stores.

JD X unmanned store in Beijing's Jianguomen district moves from high-tech (left) to low-tech (right).

Meanwhile, near the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda in Xi'an, I found an operational JD X store with RFID tags (Radio Frequency Identification) and facial recognition. What was remarkable about that store was that it was closed on the first day I visited it, while one of the unique selling points of such a store was supposed to be that it could be open 24/7.

A closed JD X store in Beijing (left) and an operational store in Xi'an (right).

Others

But there was more. In April 2018, I visited another unmanned store: the Suning BIU store in Wujiaochang, Shanghai. That month, a very helpful Suning employee gave me a detailed explanation of how the concept worked (see a demo video here).

He had to admit that, although the store seemed to work well from a technical perspective, few people actually used it. The store’s assortment, consisting mainly of merchandise of soccer club Inter Milan, which Suning owns, was too limited to attract many visitors. People who shopped at Suning, a store known for its wide range of consumer electronics, were not necessarily looking for this merchandise.

When I returned to the store in October 2018, I found the camera system for facial recognition had been switched off. The store was no longer operational at that time. The staff told me that a new, larger store with a more extensive assortment would ‘possibly’ be set up soon. Before revisiting the store in March 2019, I checked with the store’s staff member, who I’d added on WeChat. He no longer worked at that location but was kind enough to check with his former colleagues. They informed him that the unmanned store had permanently closed …

No man wants unmanned?

According to data from iResearch, no less than 132 companies jumped into the new market for autonomous retail in 2017, and more than 4 billion RMB (more than half a billion euros) was invested in related start-ups that year. However, by the end of 2019, many of the players in the market of unmanned concepts had already died.

The 'unmanned shelves', such as product shelves and refrigerators from which products could be bought, were the first to disappear. But many unmanned shops had also closed their doors. Asian Review reported on several failed autonomous store concepts. At the end of 2017, there would have been 200 unmanned stores in China, but the first bankruptcies of start-ups in this sector already took place in early 2018, and brands such as Buy-Fresh Go, i-Store and GOGO closed their stores, while JD.com scaled back its ambitions.

In addition to the ill-considered investments in start-ups without a viable concept that quickly caused a shakeout, the remaining players also seemed to be struggling. In addition to competition from the growing number of convenience stores, another cause of the problem seemed to be that unmanned stores, unlike these same convenience stores, could not sell fresh or reheated products, only pre-packaged goods, chilled drinks and sometimes ice creams. Not only is the choice and service at convenience stores greater, but it is precisely the fresh products and hot snacks and drinks that generate the most profit; margins on those products are up to 50%, while pre-packaged goods yield a maximum margin of 25%.

In an article, the WeChat media account ecxinwen cited another possible reason for the industry's troubles. Unmanned stores are trying to replace the cashier with AI, but labour is still needed for stocking and cleaning. The savings, therefore, only concern the cashier, one of China's lowest costs. In major cities, a cashier earned RMB 3,000 – 4,000 ($380 – $510), low costs compared to all the technology the unmanned stores are equipped with.

But the experiments did not stop yet in 2019. For example, Aiquna opened an Amazon Go-like store in Shanghai that worked with 5G technology. And F5 Future Stores, which had robots preparing noodles and hot drinks, seemed to have solved one of the problems of unmanned stores, receiving a capital injection. From the Top 10 unmanned store concepts that Technode compiled in 2017, it was the only company that received an investment in 2019. The remaining nine players received their last capital in 2017 or 2018.

I also found it remarkable at the time that for all its talk about New Retail, Alibaba never rolled out unmanned shops. But they did experiment with the unmanned Tao Café for four days during the Taobao Maker Festival in 2017 and also exhibited its futuristic Tmall Future Store during the Yunqi Computing Conference in 2018. Maybe the experiences with those experiments and Sun Art’s Auchan 1 Minute gave them enough insights to not even bother. Competitor Tencent's unmanned store was never rolled out either. It’s almost like the ‘big boys of New Retail’ didn’t believe in the concept…

What’s left in 2023?

And then zero-Covid was lifted, and one of our previous customers for study tours asked us to provide a new tour in October 2023. I was delighted to be able to offer them again but wondered how much of the 2019 program would even still exist. At the same time, the past three years have brought a lot of new developments. So, armed with the old program and a lot of desk research, we set off for three weeks of location scouting in June 2023…

(Note: the section below is only available to paid Tech Buzz China subscribers)