Why China Won’t Get Its Nvidia

Cambricon, Moore Threads, MetaX and Biren face a market that rewards continuity over ambition.

Content

1. Can the supplier maintain delivery continuity when external conditions change?

2. Has the vendor made it into customers’ long-term system plans—or is it still a stopgap?

Cambricon: Closest Approach to a De-Facto Platform

Moore Threads: On the Shortlist, Rarely the Default

MetaX: Built to Fit In, Not to Anchor

Biren: Aiming for the Hardest Tier, Facing the Hardest Test

Things That Caught Our Attention

New explainer videos:

China’s internet companies push further into the supermarket sector

China added 315GW of solar and 119GW of wind power capacity to the grid in 2025.

SCMP Techcast: the great AI schism (with Rui Ma)

Inside China’s Real Advantage: Manufacturing at Scale (by Rui Ma)

Introduction

The AI race is, at its heart, a contest for computing power and in the end, for chips. With U.S. export controls tightening and restricted products such as H20, B20 and RTX Pro repeatedly moving in and out of reach, China’s AI-chip industry has entered a pragmatic new phase: self-reliance is accelerating by necessity, even as a stable playbook remains elusive. Over the past year, competition has shifted from benchmark tables and launch-stage comparisons to the constraints of order cycles, project delivery and compliance boundaries. China has not been left “without chips.” Instead, export controls have reshaped how computing power is valued, shifting attention away from peak specifications toward system viability, migration costs, and uncertainty.

“Domestic substitution,” in this setting, is less a straight-line catch-up than a search for sustainable commercial deployment under constraint. The question is no longer who can match Nvidia on performance alone, but who can assemble hardware, software and system integration into solutions that work in practice and endure.

Cambricon, Moore Threads, MetaX and Biren illustrate four distinct paths. Cambricon has earlier traction in government and AI data-center projects; Moore Threads is building toward a full-function GPU and broader ecosystem reach; MetaX emphasizes engineering usability and easier migration; Biren targets high-end training from the outset. Their divergence suggests that market position will hinge not just on technical ambition, but on fit with customer structures, project economics and external limits.

This article evaluates the four companies within a single framework, not to crown a “winner,” but to assess which capabilities are most likely to be repeatedly validated and to emerge as default choices as the market moves from speed-driven expansion to structure-driven consolidation.

Enjoy reading!

Yours sincerely,

Rita Luan

After Nvidia’s Exit

With China’s push for domestic substitution accelerating, the past year has marked an unusually steep expansion phase for the country’s AI chip industry. Companies such as Cambricon, Moore Threads, MetaX and Biren Technology have moved rapidly into the spotlight, repeatedly measured by investors and the media against Nvidia, as if the market were running a race to crown an heir.

Moore Threads completed its STAR Market IPO review in just 88 days and made its public debut on Dec. 5, 2025. MetaX followed less than two weeks later, listing on the STAR Market on Dec. 17. Almost in parallel, several peers turned to Hong Kong: Biren Technology debuted on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange’s main board on Jan. 2, 2026, becoming the city’s first publicly listed GPU company, while Enflame Technology listed in Hong Kong on Jan. 8. Meanwhile, Tencent-backed Suiyuan Technology saw its STAR Market IPO application formally accepted by the Shanghai Stock Exchange on Jan. 22.

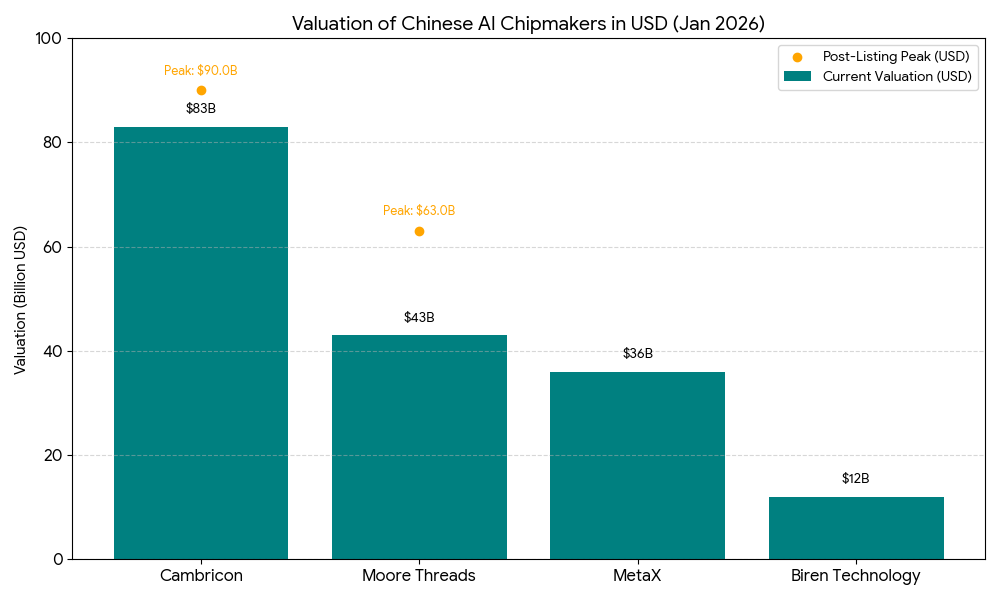

Capital markets have been quick to price in that expectation. As of January 2026, the combined market value of these four companies exceeds 1.3 trillion yuan (≈$186 billion), using early-2026 exchange-rate averages. Cambricon’s enterprise value briefly climbed to roughly 630 billion yuan (≈$90 billion) and still hovers near 580 billion yuan (≈$83 billion), making it the most prominent AI chipmaker in China’s A-share market. Moore Threads reached a post-listing peak above 440 billion yuan (≈$63 billion) and now trades around 300 billion yuan (≈$43 billion). MetaX carries a valuation of about 250 billion yuan (≈$36 billion). Biren Technology, which listed in Hong Kong in early 2026, commands a market capitalization of roughly HK$90 billion (≈$12 billion). On paper, the message is clear. Investors are making an early and costly bet on which company will emerge as China’s core supplier of AI computing power.

The Real Map of China’s AI Chip Market

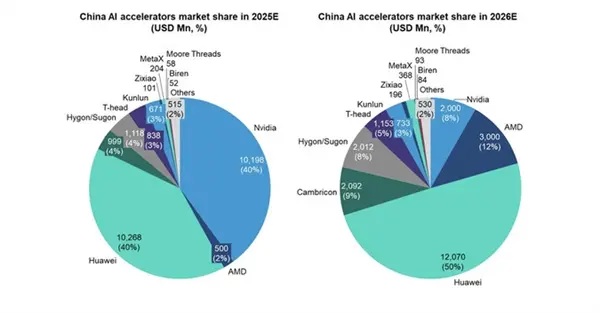

What ultimately reshapes the competitive landscape is not valuation, but who actually absorbs the demand left behind after Nvidia’s retreat. Recent research from Bernstein offers a stark view of that redistribution. The firm estimates that Huawei’s share of China’s AI chip market rose rapidly to about 40% in 2025 and could expand to around 50% by 2026 as export restrictions tighten further. Over the same period, Nvidia’s market share in China is expected to shrink to single digits—around 8%. Bernstein also estimates that Cambricon’s share stood at roughly 4% in 2025, rising to about 9% in 2026, making it one of the most visible domestic players outside Huawei.

Nvidia’s founder and chief executive, Jensen Huang, has publicly acknowledged this displacement. Under the impact of U.S. export controls, Nvidia has effectively exited China’s data-center AI chip market, with its local market share collapsing from a historical peak of roughly 95% to near zero. Yet Mr. Huang has also emphasized that demand itself has not disappeared: by 2026, he expects China’s AI chip market to reach about $60 billion. In other words, the market continues to expand, even as leadership shifts.

The critical point, however, is that Nvidia’s exit does not automatically translate into gains for domestic Chinese suppliers. Bernstein’s forecasts show that part of the displaced demand is being split between Huawei and AMD. AMD’s share of China’s AI chip market is estimated at around 2% in 2025, with the potential to climb to approximately 12% in 2026.

AMD’s continued presence in China is not the result of a relaxed policy environment, but of a deliberate willingness to absorb higher compliance costs.According to Wired, AMD Chief Executive Lisa Su said the company is prepared to pay about 15% in additional U.S. government taxes or fees on chip sales destined for China in exchange for export approvals, effectively treating regulatory compliance as a cost of maintaining market access. The move reads less like a geopolitical carve-out than a commercial calculation: pay to remain in the market.

Two Markets: Sustaining the Installed Base vs. Building New Capacity

Nvidia’s pullback has not eliminated demand in China. It has split it. Existing data centers and production codebases favor solutions with the lowest switching costs—a dynamic that helps explain why AMD has retained a foothold. Most Chinese AI chipmakers, by contrast, are competing not for one-to-one replacement in legacy systems, but for new capacity.

That distinction matters. Between 2024 and 2025, hundreds of AI computing centers, national computing hubs and large-scale data-center projects entered construction or planning across China, with total investment running into the trillions of yuan. The market has effectively bifurcated: one segment focused on sustaining existing systems, the other on building computing infrastructure from scratch. It is the latter that will largely shape the prospects of domestic GPU vendors.

Public data indicate that as of August 2024, more than half of AI computing projects, whether operational, under construction, or planned, were led by local governments and state owned telecommunications operators. Internet and cloud companies accounted for roughly 17.7% of projects by count, with the remainder distributed among independent data center operators, local state investment platforms, industrial companies building in house capacity, and research institutions.

Analysts project that investment in China’s intelligent computing center market will reach about 288.6 billion yuan (≈$40 billion) by 2028, driven mainly by local governments and state-owned telecom operators.

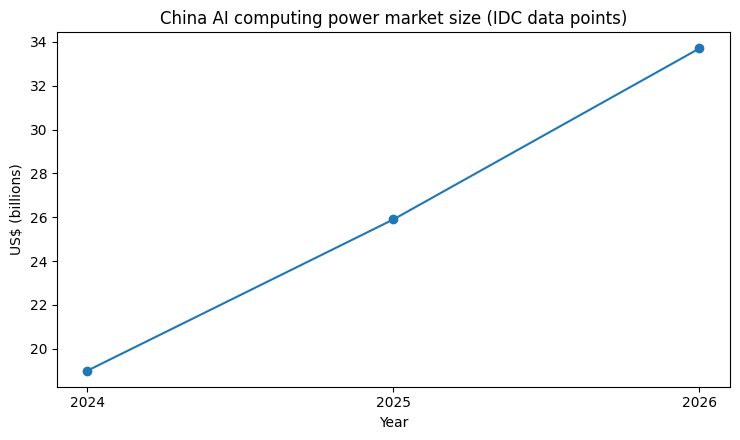

(The chart shows IDC’s estimate of China’s AI computing power market size rising rapidly over a three year period. According to IDC, the market is valued at about $19.0 billion in 2024, is projected to grow to $25.9 billion in 2025, and is expected to reach $33.7 billion in 2026. )

These groups follow a different procurement logic. New projects led by governments or state-owned entities are not designed to preserve software continuity, but to build auditable systems end-to-end. What is being purchased is not a GPU, but an engineering solution covering approvals, budgeting, centralized bidding, system acceptance and long-term operations. The questions are basic: Can it be delivered on time? Who bears responsibility when it fails? Will supply still be available years later?

Internet companies operate under a narrower calculus. Their demand is large, but decisions hinge on engineering efficiency, migration costs and speed of deployment. Despite years of policy support, Chinese GPUs have made limited inroads: roughly 3% penetration excluding Huawei, and under 15% including it. Compatibility and total cost of ownership matter more than origin.

This divide helps explain the divergent trajectories of Cambricon, Moore Threads, MetaX and Biren Technology. In a market shaped by project-based procurement and long operating cycles, China is unlikely to produce a direct “Nvidia replacement” anytime soon. The decisive contest is not over peak specifications, but over execution: the ability to deliver reliably, win repeat bids and convince customers to commit long-term capital and organizational resources to a platform.