Key takeaways:

Xiaohongshu has been able to change its average user profile and doubled the monthly active users it had in mid-2020.

Its monetization through e-commerce has been limited, but it has implemented new advertising formats to grow its business with brands and merchants.

Xiaohongshu has made it easier for content creators to monetize their accounts by lowering various barriers to entry for brand promotion and e-commerce.

Xiaohongshu continues to have to balance commercialization and user experience.

Chapter 1: An introduction to Xiaohongshu

Chapter 2: Changing course (paid content)

Chapter 3: Other recent developments (paid content)

Note: If you are still getting familiar with the history of Xiaohongshu, please read the background information in Chapter 1. If you are well-informed about the company's background and want to save time, proceed to Chapter 2. You can also listen to Tech Buzz China's 2018 episode on XHS and read Rui’s 2021 thread on Tech Buzz China Insider here.

Sources: The chapter 'Introduction to Xiaohongshu' is based on an earlier (Dutch) article Ed wrote about XHS. Chapter 2 is sourced from exclusive expert interviews in the Six Degrees Intelligence database unless other sources are mentioned in annotations between brackets. Chapter 3 includes noteworthy recent news on Xiaohongshu from (Chinese) media.

Chapter 1: An introduction to Xiaohongshu

Xiao Hong Shu (小红书) was founded in Shanghai in 2013. The platform's name means 'little red book' in Chinese and, according to the founders, has nothing to do with the famous booklet of Mao Zedong's quotations. In English, they simply call their platform RED. For this article, we'll stick with 'XHS.'

Initially, the social platform was a community where consumers, especially young females, shared their experiences with foreign (luxury) products and tourist destinations. Users, who call themselves 'Little Sweet Potatoes' (a homophone of 'Little Red Book' in Chinese), post photos and reviews of products, give each other tips, and share comments. In a society where peer reviews on social media and social networks inspire more trust than other forms of product information, XHS quickly became a highly regarded platform.

The platform feels like a cross between Pinterest and Instagram but with buying options and longer, blog-like content. In XHS, a post can have up to 9 pictures and 1,000 characters. Considering that in written Chinese most words consist of just 1 or 2 Chinese characters, you can tell quite a story within those limits. Readers can 'like' posts, post comments, and share content with others on other platforms (e.g., Weibo and WeChat). XHS does not want users to 'spam' each other on its platform and lets its algorithm determine which content is of interest to individual users. Also noteworthy is the feature that enables users to collect others' posts and save them for future use, comparable to Pinterest's 'boards.'

From shopping guide to online store

Originally, XHS was mainly a 'shopping guide,' first as a set of downloadable PDFs and later as a forum. Users on XHS could compile a shopping list of products they wanted to buy when going abroad. Once they arrived in another country, XHS would point them toward interesting shops and locations through the 'Nearby' function in the app. If the clothing sizes in that country were different, the app would provide conversion tables, and if you didn't know how to ask if you could try something on in the local language, the app had the proper translation for you.

Products that appear in users' newsfeeds could often be bought directly on the platform. Initially, these sales were primarily made by so-called daigou, mostly Chinese students who buy products abroad and send them to consumers in China. The products reviewed on XHS were sought after but often unavailable in China. At the end of 2014, when the cross-border e-commerce market was growing, and the founders of XHS realized that some products were very popular, they decided to cut out the daigou and turn the platform into a cross-border e-commerce platform.

XHS partnered with prominent foreign brands in popular product categories such as cosmetics, health, food, and household goods. XHS began to source these items and sell them on the platform. In contrast to Alibaba's marketplaces (Taobao and Tmall), this self-operated e-commerce model meant that XHS had products in stock that it shipped to customers. They thus guaranteed product quality in a country where counterfeiting remains a persistent problem when shopping online.

Users regularly visit XHS to see what interesting new content can be found in the accounts they follow. The app's homepage is personalized by the algorithms based on previously visited content. In another user scenario, users are actually looking for information about a specific product. In the online shopping section of the app and website, some products can be purchased in XHS's own shop or third-party shops hosted by XHS. In 2017, the division between XHS and third-party sales was approximately 50-50. Shoppers could chat with store owners and pay with WeChat Pay or Alipay. However, many users would research XHS and then purchase the product elsewhere.

While XHS' market share in the cross-border commerce market was smaller than its major competitors (see chart below), setting up an online shop on XHS was more straightforward and less costly than on major platforms such as Tmall Global and JD Worldwide. The operational costs are substantial though: brands paid XHS to host their shop ($1,250 – $7,500 per month), and at the time, the platform charged a hefty 15-20% commission on their sales.

When some prominent Chinese celebrities, such as movie star Fan Bingbing, started using the platform and XHS sponsored two popular reality TV shows in 2018, it brought the platform more brand awareness and increased user numbers.

KOLs and marketing

Brands can open their own official brand accounts and use them to build brand awareness and sell products. With a brand account, they can also respond to existing posts and discussions on the platform and thus participate in the conversations of (potential) customers.

On top of this, XHS also regularly organizes sales campaigns, flash sales with temporarily available offers, and other promotions in which brands can participate for a fee. Like most e-commerce platforms, XHS has a series of unique shopping festivals throughout the year. It also piggybacks on Alibaba's 11-11 (Singles Day) festival.

As mentioned, in its early years, users of XHS were generally young women under the age of thirty. They read fellow users' reviews or follow Key Opinion Leaders (KOLs, China's term for influencers) who promote products. These KOLs are often users who have built up a loyal following through their reviews and advice. XHS eventually started using these influencers to sell products, earning the KOLs a commission. To facilitate this, XHS opened a platform, Pugongying (蒲公英, literally 'Dandelion'), that brings together KOLs and brands.

By 2019 XHS worked with around 8,000 verified brands and 4,800 influencers, and three types of KOLs could be found on XHS:

Loyal users of the platform who shared lots of content and built a group of loyal followers.

Influencers from other platforms, such as Weibo and WeChat, who added XHS to their communication channels.

Celebrities who use the platform to build a more personal connection with their fans.

Depending on the reach of a KOL, costs could range from a few hundred to more than $10,000 per post.

Because of this commercialization, many users of XHS became skeptical of the platform and the objectivity of KOLs. Soon the platform suffered from fake product reviews and fraudulent content scandals. The government also accused it of illegally harvesting data. As a result, XHS was removed from Apple and Android app stores for more than three months in 2019.

Initially, XHS tried to uphold its reputation as a reliable content-driven platform by not allowing brands to place banners and other advertisements. As we will see in Chapter 2, this strategy has drastically changed.

These limitations made using KOLs and sponsored posts by brands the best marketing method through the platform. XHS did however limit the share of sponsored posts that a KOL could send to about 20%. KOLs with more than 5,000 followers also had to register sponsored posts with the platform, and the post itself had to show that it contained sponsored content. The administrators of the platform also regularly remove posts that are too sales-oriented.

XHS's value lies not so much in its role as a sales platform but as a source of information for consumers who do online research before purchasing. While browsing, users regularly come across exciting products they decide to buy elsewhere. Especially for cosmetics, XHS proved a good source of information, so even if the consumer subsequently purchases another platform such as Tmall or WeChat, XHS proved a unique marketing tool for brands.

However, for XHS itself, the focus on quality content was problematic for the revenue model. Since sales mostly happened on another platform, XHS earned very little from this. In 2018, XHS therefore no longer allowed posts asking people to purchase products on other sites or the use of hyperlinks to such third parties.

Cooperation with Alibaba

In May 2018, Xiaohongshu raised $300 million from investors such as Alibaba and Tencent. The platform had grown to 100 million registered users, of which 30 million were monthly active (MAU). A year later, the counter stood at 150 million registered users, of which 84 million are active monthly.

Alibaba's Taobao is a marketplace that suffers from many fake reviews. An XHS review for a product was considered a more reliable reference (even though XHS removed more than a million paid reviews from its website in early 2019). According to Miranda Qu, one of the XHS founders, the platform had already been used as an information source by 14% of people who wanted to buy fashion items on Taobao. In addition, Alibaba has always struggled to set up and integrate a truly reliable social network into its e-commerce platforms.

At the end of 2018, Taobao started incorporating XHS product reviews into its platform, clearly marked with the XHS logo. Sellers could add XHS content to their product pages, and Taobao's algorithm would then select some of the available reviews. By the way, those could just as well be a negative reviews. The question remains what the effect has been on the quality of the reviews on XHS as they became important to sales on Taobao.

New initiatives: live streaming, mini-programs, and New Retail

By 2019, XHS was much more than a cross-border commerce community. Instead, it had become a lifestyle platform where the cross-border aspect was no longer leading. With the explosion of short video use in China in the second half of the last decade, it was not surprising that short videos also gained a prominent role on XHS. These were often short instructional videos, such as how to cook your favorite dishes at home.

The platform already had several mini-programs on WeChat. Still, it developed a mini-program called Xiaohongdian, which gave users discounts when sharing products with friends on WeChat (suspiciously similar to Pinduoduo's early social commerce model). In 2018, XHS also launched its own design brand, REDesign. It also jumped on the new retail bandwagon by opening an offline store called REDhome in Shanghai's Joy City shopping mall, followed by a second Shanghai store and more stores in Suzhou, Hangzhou, and Ningbo. In 2020 it shut down both Shanghai stores, calling the initiative an experiment. At the time of writing, no XHS stores could be found in the mentioned cities on Dianping.

In the summer of 2019, XHS started experimenting with livestreaming, rolling it out in November of that year. It selected several KOLs based on the quality and frequency of their content and their number of followers and started testing livestream videos with them. For a platform that relied so heavily on influencer content, it was remarkable how late XHS caught on to a trend that, at the time, was already several years old in China.

According to a report by marketing agency WalktheChat, 90% of e-commerce sales on XHS are generated through live commerce. While the total GMV is very small compared to other players in the live commerce market, the average order value tends to be much higher on XHS, driven by the large share of luxury items and the supposed reliability of the livestreamers.

2019 also saw XHS spending money on customer acquisition for the first time, having previously depended on organic growth based on content. LatePost reported (link in Chinese) how the platform gained a lot of new users through advertising and pre-installments on smartphones.

At the start of 2020, XHS announced it was lowering its entry barriers for merchants to open shops. Previously only trademarked brands had been allowed to open a store on the platform, but now anyone with a business license could start selling on XHS.

At the RED for Future Conference in July 2020, XHS downplayed its e-commerce initiatives and unveiled its new strategy to enable brands to promote themselves on the platform. Platform commissions were reduced from 20% to 5% (comparable to what Tmall charges fashion and cosmetic brands). At the same time, XHS also implemented traffic funnels to promote brands and livestreamers and more ways for merchants to connect to reviews of content creators with large followings.

Since mid-2020, XHS has doubled its monthly active users to more than 200 million. It is one of the few internet platforms with a YoY user growth rate of over 30%. Other internet companies are trying to copy the XHS model (Bytedance unsuccessfully tried with apps like Xincao, Kesong, and Douyin Box).

In July 2021, XHS was among a group of internet platforms that received undisclosed fines from the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) for hosting content deemed "harmful to the physical and mental well-being of minors."

When we last wrote about XHS in mid-2021, it was rumored that the company's 2020 revenue was $600-$800 million in advertising income, and it had ~$1 billion e-commerce GMV. XHS had missed its revenue targets for 2018 and 2019, its self-operated e-commerce was thought to have largely failed, and it was refocusing on livestreaming.

Time for an update.

Chapter 2: Changing course

Let’s start with some key figures.

After XHS launched in 2013, it grew very slowly compared to other Chinese apps. It's only in recent years that its growth has accelerated.

By the end of 2020, Xiaohongshu had 120-130 million monthly active users (MAU) and a peak of 90 million daily active users (DAU).

In 2021 the average number of DAU grew from 44 million in 2020 to 60 million.

By September 2022, the DAU had reached 80 million, and XHS aimed to increase that number to 100 million by the end of the year.

By the end of 2022, XHS had 200 million monthly active users, including almost half a million monthly active content creators, an increase from 290,000 in November 2020.

XHS works with more than 2,000 MCNs (Multi-Channel Networks), of which 600 are certified, an increase from 368 in November 2020.

Before 2020, a monthly active user opened the XHS app 7-8 times a month, while Douyin and Kuaishou were at 12 times a month. By mid-2022, XHS's monthly open rate had also increased to 12.

Before 2020, daily users spent about 25 minutes a day on XHS, increasing to 57 minutes by mid-2022.

Changing user profiles

XHS's user profiles changed dramatically after 2020. Before 2020, XHS was a high-end platform dominated by female users, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:9. Mid-2022, already 30%-35% of users were male, and the platform expected this to increase to 38% by the end of 2022. XHS accomplished this gender shift by adding more male-oriented content (trendy sports, cars, finance, popular science, etc.) and recruiting new users in male-oriented communities.

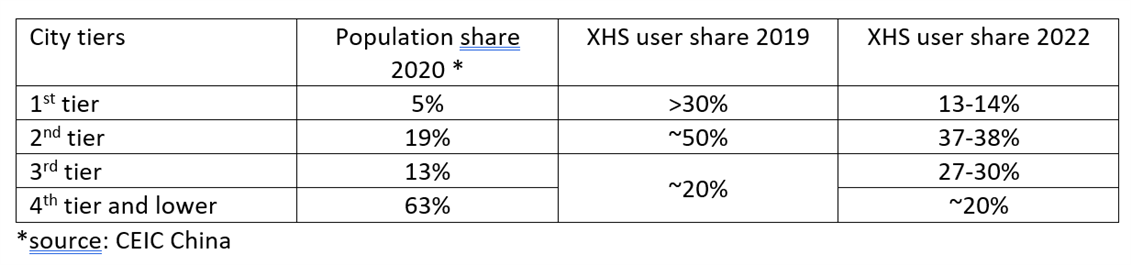

When it was still focusing on cross-border shopping guides and e-commerce, XHS's users lived mainly in first-tier cities. After 2020, the share of users from second and third-tier cities grew strongly. The percentage of first-tier city users dropped from more than 30% - for reference, only 5% of China's population live in these same cities – to 13-14%.

As such, XHS has now become a platform focusing on 2nd and 3rd-tier city dwellers, supplemented by 1st-tier citizens instead of the other way around.

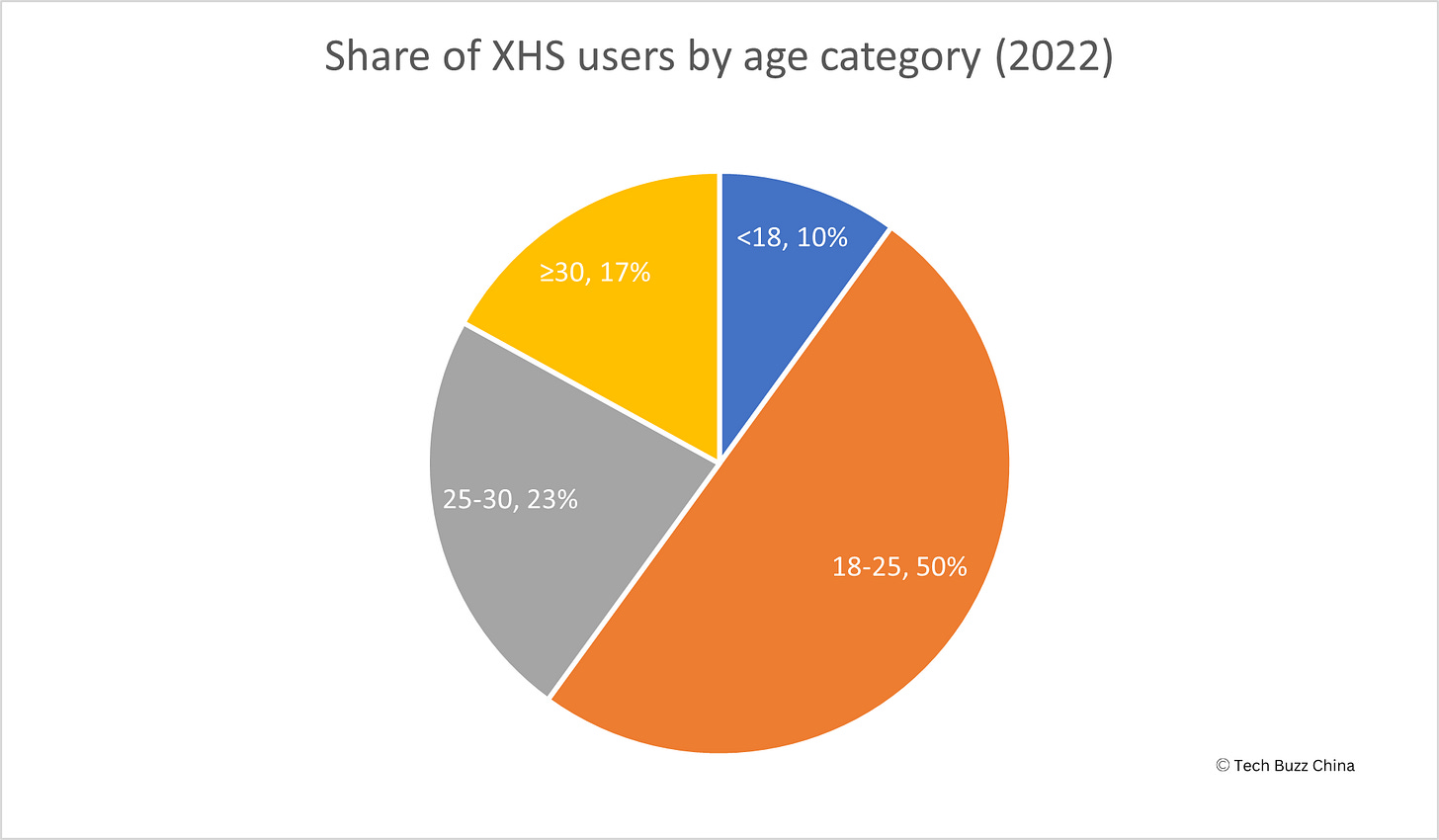

The average age of users had also decreased substantially. Before 2020 most users were 25 to 35 years old. Now 83% are younger than 30 years. XHS users over 35 only make up a few percent of the app’s user base. Therefore, the ‘average XHS user’ is now a university student or recent graduate with 2-3 years of work experience.

Changing content

As mentioned, the time daily users spend on XHS increased from 25 minutes in 2020 to 57 minutes by mid-2022. Growth in the richness of content and vigorous promotion of videos by the platform can explain this. Nowadays, the XHS homepage consists of 60% videos and 40% posts with pictures.

Nowadays, content is much less related to luxury items and showing off wealth. The three most popular content categories have changed from fashion, beauty & skincare, and home furnishing before 2020 to fashion (including trendy lifestyle, camping/glamping, etc.), food, and 'relationship content.' Other categories with increasing popularity are fitness, knowledge, and pets.

While the average user might have flaunted less wealth, XHS successfully leveraged celebrities in their content and had actresses like Fan Bingbing and Zhang Yuqi showing off their wardrobes and jewelry. For the male audience, XHS has collaborated with influential people from the hip-hop and e-sports scene.

XHS wants to have a monopoly on content on some celebrities or at least wants them to share exclusive content that can't be found elsewhere. The platform also wants to be the go-to place for information on trendy foreign celebrities (e.g., the Kardashians), content that can't be found on other social media platforms in China. This way, XHS saves users from having to use a VPN to watch content of foreign stars on platforms like Instagram.

Users have started to view XHS as a content platform comparable to Douyin and Kuaishou, where they go to kill time and be entertained. Before 2020 users mostly came to XHS to solve a problem, do product research, and look for specific content. [We previously reported that XHS posts have a remarkably long lifespan of sometimes over one month, partially driven by search and algorithms]. While 80% of the daily users used to come to the app with search queries, this has nearly halved to 43%. [LatePost reported (link in Chinese) that 60% of visitors to XHS come with a search query, while this is only 30% for Douyin and Kuaishou].

These changes are reflected in XHS’s changing slogans. It used to be a more self-promoting ‘Come to XHS to record your life’ but changed to a more global perspective of ‘Come to XHS to find good things in the world and the life you want.’

Adding New Verticals

After 2020, XHS started adding various verticals, among which 'food' and 'mother & baby,' and became the leading platform in the latter category after acquiring users interested in this content.

Since XHS started as a shopping guide for foreign destinations, its original content categories were fashion, beauty, and foreign destinations; logical choices because that's what Chinese travelers mostly buy abroad. By 2019 some of the earliest XHS users were becoming young mothers. When baby-related content started going viral and research confirmed that part of the users had information needs about maternity and baby care, XHS decided to add a 'mother & baby' vertical.

Another vertical, ‘food,’ was added during the pandemic after recipe posts started to go viral. Adding new verticals is considered a strategic decision, and new ones are only added quarterly or annually.

In 2021 XHS entered the territory of Meituan (Dianping) by starting ‘local life’ and ‘travel’ verticals and invited several relevant celebrities to open XHS accounts. The platform filled the content void online travel agencies (OTA) left regarding travel tips and knowledge. XHS also started adding local services content, but only for the cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Chengdu. However, the lockdowns of the zero-covid policy slowed growth.

Compared to Dianping, XHS has stronger ‘zhong cao’ (种草) features. Zhong cao translates to ‘seeding grass’ and refers to peers and influencers recommending products and services that trigger strong purchase intentions among their followers. Brands ‘seed’ content on various platforms to build brand and product preferences among their target audiences.

Verticals that XHS focused on in 2022 were ‘travel’ and ‘trendy sports.’ The latter is aimed at males, and high-income users since the costs of outdoor sports are high. It also started putting more emphasis on ‘general knowledge’ videos when it found that users watching that type of content spent more time on the platform. [LatePost recently reported that XHS's algorithm gives more weight to videos with helpful information than those just aimed at entertainment and 'killing time'].

Content creators

XHS uses the following categories of content creators:

Amateurs – 0-1,000 followers. 'Amateurs' don't get support, but XHS watches this group for potential new KOLs by looking for well-performing posts in various content categories or creators quickly gaining followers. XHS screens the logins and number of posts per month of amateurs. XHS staff will send the more active ones private messages to encourage them and suggest hot topics or invite them to write about restaurants, hotels, etc., in exchange for free products or services.

If a specific creator matches the development of a key vertical category, they are invited to a WeChat group with like-minded creators. XHS will share popular searches within these groups, making it easier for the group members to create posts with a high chance of becoming popular. Group members can also receive training on content creation.

XHS also invites these creators to social events, like visits to the XHS offices, roadshows, and government/media events. These (still) unpaid creators can add free exposure to such events while becoming friends and reinforcing each other's growth.

In the meantime, XHS operators help key brands like L'Oreal, Estee Lauder, Chanel, and LV to select creators from this group without having to use the Pugongying (Dandelion) platform.

Pre-KOL (previously called KOCs; Key Opinion Consumers) – 1,000 – 5,000 followers.

KOLs (Key Opinion Leaders) - >5,000 followers. XHS will sign exclusive contracts with some creators in this category. The rules can be stringent. A relatively small number (about 100) of top-level KOLs are not allowed to open accounts on other platforms. The second-level KOLs sign a contract with Pugongying (Dandelion). They can open accounts elsewhere but cannot share identical content on these other platforms. Other requirements refer to the number of posts they need to publish and how posts are written. XHS sometimes acts as a broker between the KOLs and brands.

Pugongying contractors are managed by an XHS subsidiary named Hongmeng Culture. Some of these second-level KOLs will be supported with traffic resources. They will be prioritized for brand promotions, or XHS might provide free resources and an MCN team (Multi-Channel Network, basically a KOL production agency) to help them create higher quality or higher frequency videos.

Celebrities: Celebrities are handled separately from amateurs and (pre-)KOLs. Only stars that have made their official TV debut are considered celebrities. If they haven't appeared on TV, they won't be categorized as such, even if they have millions of followers (top-selling Taobao live commerce host Li Jiaqi, a.k.a. Austin Li, is an example of someone not considered to be a 'celebrity' by XHS's standards).

Recruitment of celebrities is not so much aimed at improving the traffic of a vertical but at increasing the popularity of XHS as a whole so it can compete with Douyin and Weibo for the users' attention. It also aims to attract younger users (teenagers and users in their early twenties).

Amateur creators can only accept free advertising and free promotions. But last summer, XHS lowered the threshold to be considered a pre-KOL from 3,000 to 1,000 because only pre-KOLs and KOLs can use the Pugongying advertising platform for monetization. In other words, more creators can now accept paid promotions for brands.

XHS encourages talents to open stores for further monetization and has lowered the barrier to entry. If the turnover is lower than RMB 10,000, XHS will not charge any commission fees. For stores that use live commerce, the commission is just 3%. XHS has invested in several emerging and new consumer brands or acted as their agent. It can negotiate contracts with these brands for creators.

The KOL category is further grouped into 'head' (those with >1 million followers), 'head to waist' (500,000 – 1 million followers), 'waist' (300,000 – 500,000 followers), 'waist to tail' (100,000 – 300,000) and 'tail' (<100,000). Unlike Douyin and Kuaishou, who send a lot of traffic to top creators, XHS focuses on the 'waist & tail' group for cultivation and training and links them to specific verticals.

Previously, XHS tried supporting mainly the 'head' KOLs but found that ordinary users lost interest in content creation because it was hard for them to grow. It also damaged the traffic to some verticals since top KOLs tend to focus on the same type of verticals: beauty, fashion, and to a certain extent, home furnishing. With smaller KOLs, XHS can also build out other verticals.

Furthermore, focusing on 'head' KOLs also hurts the conversion rate of some merchants since consumers lost trust in celebrity endorsements and tend to believe their peers' – the less popular content creators - opinions instead. While merchants pay a lot for 'head' KOL endorsement, the smaller KOLs are cheaper and often perform better. According to XHS, the way they work with these smaller KOLs makes them feel at home in the XHS 'family.'

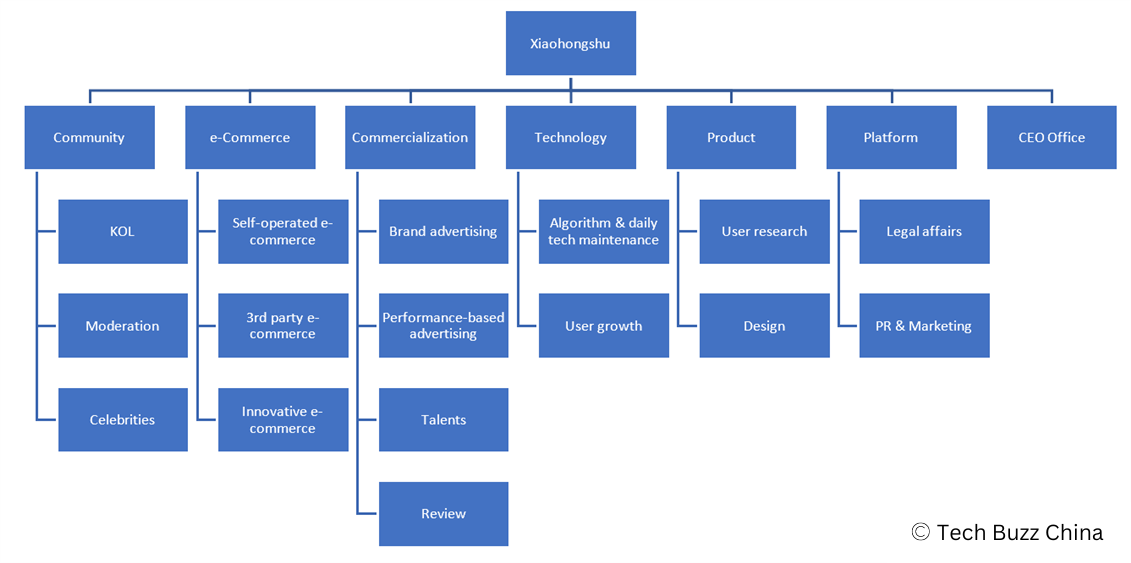

Corporate Organization

Besides departments common in every company (e.g., HR, Finance, ICT, etc.) XHS is organized into the following first-level departments.

Community Department: responsible for the content output of XHS and operation of verticals (food, mother & baby, etc.). Responsibilities are:

KOL creation & cultivation management.

Community moderation (organized in sub-departments by vertical like beauty care, fitness, etc.).

Celebrity recruitment & operation. XHS plans to set up a separate department for live broadcasting and recruitment of overseas celebrities.

E-Commerce Department (merged with Community Department in 2022), responsible for:

Self-operated e-commerce (P&L, customer service, logistics)

Third-party e-commerce (e.g., helping Taobao merchants operate on XHS)

Innovative e-commerce (XHS Mall on WeChat, second-hand e-commerce, offline stores)

Commercialization Department, responsible for all advertising business:

Brand advertising (opening screen, traffic-based advertising)

Performance-based advertising (CPC)

‘Talents’ (KOL-related content)

Review team (checks advertisements and commercial posts. Commercial KOL posts not run through the Pugongying system can be banned or limited in traffic. In such cases, a user might need to show proof of purchase of the product to have his account unblocked.)

Technology Department.

Product Department. The product department handles product updates and the architecture of XHS. The user research sub-department also researches internal needs, like the reasons for poor e-commerce sales.

Platform Department.

CEO Office: responsible for financing matters regarding new consumer products and brand acquisitions.

Business related to creators is managed by the community team, while the commercialization team deals with content that generates revenue.

XHS's organizational structure is relatively flat, with many first-level departments. As a result, ideas within the company can quickly be communicated to a higher-level manager or even CEO Mao Wenchao. This structure also promotes cross-departmental communication necessary for projects that involve multiple disciplines.

XHS's headquarter in Shanghai is responsible for the coordination and execution of the company's business, while the Wuhan office houses a content review team of several hundred people. The Beijing branch, responsible for developing new advertising forms, mainly employs product managers. Branches in new first-tier cities like provincial capitals are responsible for sales.

Commercialization

As mentioned in Chapter 1, XHS started focusing on commercialization in 2019, when its content was still mostly about beauty, fashion, and foreign destinations. The platform started offering advertising space for the promotion of e-commerce by merchants that had opened stores on XHS and for regular brand advertising. The latter focused on advertisers with no potential for opening actual XHS stores.

Advertising initially led to problems with small and medium-sized merchants using product placements and posting offensive content and clickbait. XHS's users started to complain about the quality of the content on the platform, which didn't know how to handle this at first.

The commercialization department ran into the dilemma that the looser the rules, the more revenue was generated. But this led to clashes within the organization and friction with the platform community. The reputation of XHS tanked, and as mentioned, it was temporarily taken off the app stores in 2019. When it returned, content management, community governance, and commercial control tightened, which proved highly necessary since some individual XHS users had started doing business from their accounts.

By 2020 XHS seemed to have found the right balance, and commercial content had come in line with community content. Commercialization started to be strictly regulated, and more staff was recruited to help with product selection and content output.

In 2020 XHS also increased the proportion of brand advertising. The adjusted business approach worked, and as can be seen in the chart below, revenue from commercialization started skyrocketing.

Advertising remains the primary source of income for XHS and consists of the following three categories:

Brand advertising: e.g., opening screen advertising, targeted newsfeed placements on the Discovery page, charged based on the number of clicks.

Performance advertising: bidding on search keywords (SEA) and placement on search result pages. Charged based on the number of clicks (CPC).

Content advertising: related to KOL content and booked through the Pugongying (Dandelion) platform that matches advertisers with content creators. XHS charges a 10% service fee (unless it has already been charged by Hongwen, XHS's official MCN organization) and 16% taxes for these posts. [As we previously reported, only little over half of the charged advertising fees end up in the pocket of the KOL].

If an advert leads to a sale on XHS, the platform charges an additional 5% commission.

Why is e-commerce not in the above pie chart showing the shares of various forms of commercialization? XHS doesn't count e-commerce as commercialization. In 2019 there was a conflict between the e-commerce and community departments because the latter couldn't provide enough traffic to the former. As a result, performance-based advertising saw little success.

There also were conflicts with the commercialization departments since merchants using performance advertising (CPC) were forced to make deals on the platform. They had to generate ROI by transactions on XHS, but the daily active user base at the time was still only 3 to 4 million. This limited the opportunities for commercialization. The restriction was dropped in 2020, and merchants were no longer forced to sell on the platform.

XHS has tried penetrating the 'sinking market' (lower tier cities and rural areas) by recruiting some young people from these regions to see if they were interested in high-end trendy sports. Revenue proved extremely poor. The local population and their tastes did not fit within the existing community.

Brand advertising process

XHS follows the following process with brands that want to advertise on the platform.

XHS determines if the advertiser has already opened a store.

If not, XHS opens a store for a brand with store potential. Advertisers with a store tend to have a higher conversion rate.

The advertiser chooses a form of advertising. Big brands tend to pick brand advertising, while advertisers with small budget pick performance-based advertising.

If applicable, the advertiser selects 5-10 KOLs, who make quotations for posts.

The advertiser signs a contract with XHS.

XHS reviews and launches the advertisement.

KOLs write and publish the posts they agreed upon with the advertiser. Once a week, advertisers select posts with good content that have proven popular to be further promoted on the XHS newsfeed. The advertiser decides the location, time, and amount of the advertising placement with XHS.

Brand partners are selected from KOLs if they have more than 5,000 followers, more than 10,000 impressions per month on their posts, and have signed a contract with an MCN.

Examples of advert prices and performance:

Dynamic full-screen advert: RMB 2.4 million per day, click rate 7-16% (depending on brand awareness and spokesperson: high brand awareness can help reach 15-16%). The app's opening (splash) screen has 30+ million impressions per day. XHS rotates three such screens per day.

Full-screen static advert: RMB 2 million per day.

Dynamic non-full-screen advert: RMB 2.2 million per day.

Static non-full-screen adverts: RMB 1.8 million per day, click rate 7-8%.

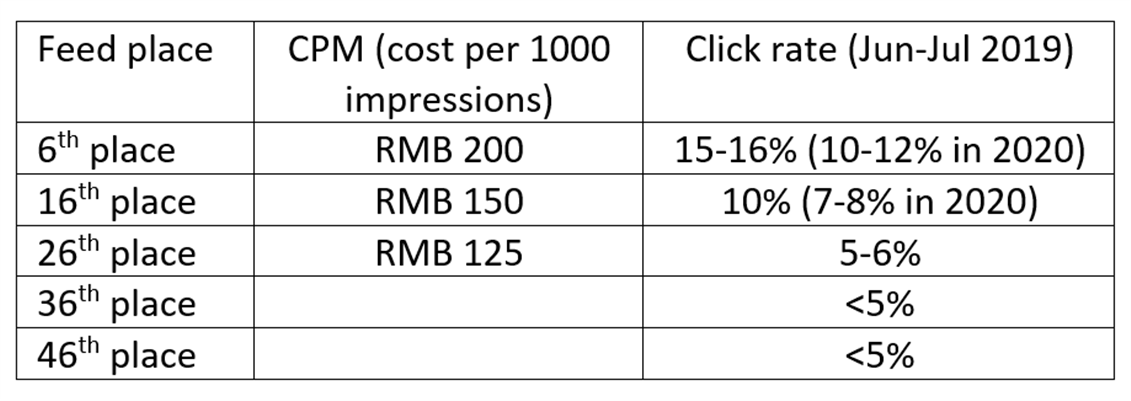

Newsfeed adverts. The price and average click rate depend on the place in the newsfeed. XHS does not guarantee a click rate, only a volume of impressions. Customers usually buy 5 to 6 million impressions. Click rates depend on the position in the newsfeed and product category: beauty care posts in 6th place had a click rate of 8-10% in 2019.

Click rates dropped between 2019 and 2020 because of user fatigue with advertisements.

Search keywords: RMB 2 million+ per day. A ‘hot search’ keyword can generate 1 million clicks per day.

Brand zone: ~RMB 300.000 for one week. XHS users can select topics to post in brand zones. The average topic receives 200-300 posts or more than 1,000 for well-known brands. General topics usually receive 10-20 million views, and high-quality topics usually get 50 million views. Success is measured by the number of posts, impressions, content quality, and user engagement.

XHS sells combinations of advertising forms at a discount.

Like many other apps, XHS also added a 'nearby' function and has rolled out a bidding model for location-based advertising after testing in 2019.

For brand advertising, 70% of the clients are direct customers, while it is 30-40% for performance-based advertising. The rest comes through agents, which take a 20-30% cut from the advertising sales.

e-Commerce

XHS's first steps into e-commerce concerned self-operated e-commerce. As early as 2014, one year after the platform's start, it was building warehouses for e-commerce fulfillment. In 2017 it introduced third-party e-commerce (marketplace). However, the community and e-commerce were separate; users would come to read product reviews on XHS and then proceed to Taobao or JD to buy the product there.

Before 2018, XHS was positioned as a community focused on cross-border e-commerce (into China) shopping strategies. After starting a marketplace, XHS transformed into a lifestyle-sharing platform and started accepting goods from traditional stores and those related to the newly introduced verticals. In the second half of 2020, XHS started allowing external links to Tmall and Ele.me [but this was already rolled back in May 2021].

In August 2021, XHS opened e-commerce to the community. Previously creators could only add a product link to a post, and XHS would handle the conversion to a purchase. Users could however lose interest in buying the product if it didn't match the post's content.

At the same time, business accounts could not directly reach users and had to use the B2K2C approach: Business-to-KOL-to-Consumer. But the advertiser with the biggest budgets, the big brands, had the loudest voice and drowned out the rest.

After the reforms, creators could tag product features, prices, and the brand's XHS account in their posts. Clicks on tags can send users to the merchant, store, product, brand, or event page. After changing the e-commerce policies, the XHS interface works more like Meituan and Dianping and is more in line with 'seeding.' High-quality creators get the right to speak and can promote small and medium-sized brands. This proved to be more effective and further helped XHS's commercialization.

Necessary improvements

Commercialization remains the primary goal of the company. The ARPU (average revenue per user; commercial income divided by DAU) remains an important indicator for the valuation of XHS, which had to shelve its plans for an IPO in 2021.

XHS’s current bottlenecks lie in e-commerce, community content, and user traffic. XHS’s shopping mall is not distinctive, and while it lacks the volume of a Taobao, it looks more and more like that Alibaba platform. While this could be profitable in the long term, it could damage the ecology of XHS. The platform, therefore, uses advertising income to make up for the lack of e-commerce income.

XHS has found it challenging to find the right balance between commercialization on one hand and community and user experience on the other. XHS's ad load (% of content that consists of adverts) is 20%.

XHS thinks it can further improve the app's stickiness and have users open it more than the current 12 times a month. XHS has a good DAU figure, but the amount of time users spend on the platform lacks far behind that of Douyin. XHS plans to optimize video and livestreams to increase usage time.

[XHS's revenue is highly dependent on advertising, with e-commerce only counting for an estimated 20% of the rest of the revenue. 2022 has shown many Chinese internet companies that too much dependence on advertising and a lack of diversification can be a substantial risk in difficult economic times when advertisers cut budgets. Like most businesses, XHS suffered slowing growth in 2022 because of the zero-covid policy. During the pandemic, the beauty and fashion markets completely stopped growing. Like many other internet companies, XHS has had to take countermeasures: it had to fire 200 employees in April, almost 10% of its staff, while the quality of meals in the cafeteria went down and complimentary drinks and snacks disappeared.]

Chapter 3 – Other Developments

In November, the Financial Times reported that Alibaba and Tencent-backed XHS had lost as much as half of its valuation in the private equity sector, from $20 billion to $10-$16 billion. After the government investigation following Didi's IPO in June 2021 and tightening regulations on cross-border data flows of foreign listings, XHS shelved its IPO at the end of 2021. It claims to have no IPO plans at the moment.

In November 2022, Techplanet reported (link in Chinese) that XHS was testing a new Clubhouse-like feature called 'Voice Live,' focusing on audio-based social networking. Users can create public rooms about a specific topic. In the rooms, you will find a host, a maximum of 11 guests, and up to 100 audience members. If audience members want to speak, they can raise their hand to be invited as 'guests.'

In January, 36Kr reported (link in Chinese) that old Chinese brands looking to rejuvenate themselves among a younger crowd are flocking to XHS. XHS users are spontaneously sharing new usage ideas for these old brands. The interaction also helps these brands to understand this target audience better. XHS uses data to support these brands in developing unique seasonal products, launch strategies, and identifying upcoming trends.

In 2022 there were more than 78,000 domestic brands on XHS, with users searching for domestic brands more than 1.2 billion times and discussing them 6 billion times. According to XHS, its rich user-generated content and real consumer insights give it a competitive edge. In 2022 it launched ‘Lingxi,’ a business data platform helping brands gain more accurate consumer behavior insights.